On December 30, 2013, MyBudget360 blog posts:

Money is only as useful as to what it can purchase. The Fed has created a system where debt is now equal to money. This is why big purchases like cars, housing, and even going to college are only feasible by mortgaging your future for many decades. Since the payments are broken down into tiny monthly installments many people pay little attention to the true cost of things over their lifetime. Yet over this time, the U.S. dollar has lost a tremendous amount of purchasing power due to inflation. Inflation slowly eats away at your purchasing power yet having access to debt has given the middle class the false impression that they are still protected from the unraveling impacts of inflation. Someone sent over a photo posted over on the popular Reddit website that shows the cost of living for people back in 1938. You would think that people in 2013 would have more purchasing power than those living through the Great Depression. Adjusting for inflation you would be surprised what has happened in the last 75 years.

The cost of living between 1938 and 2013

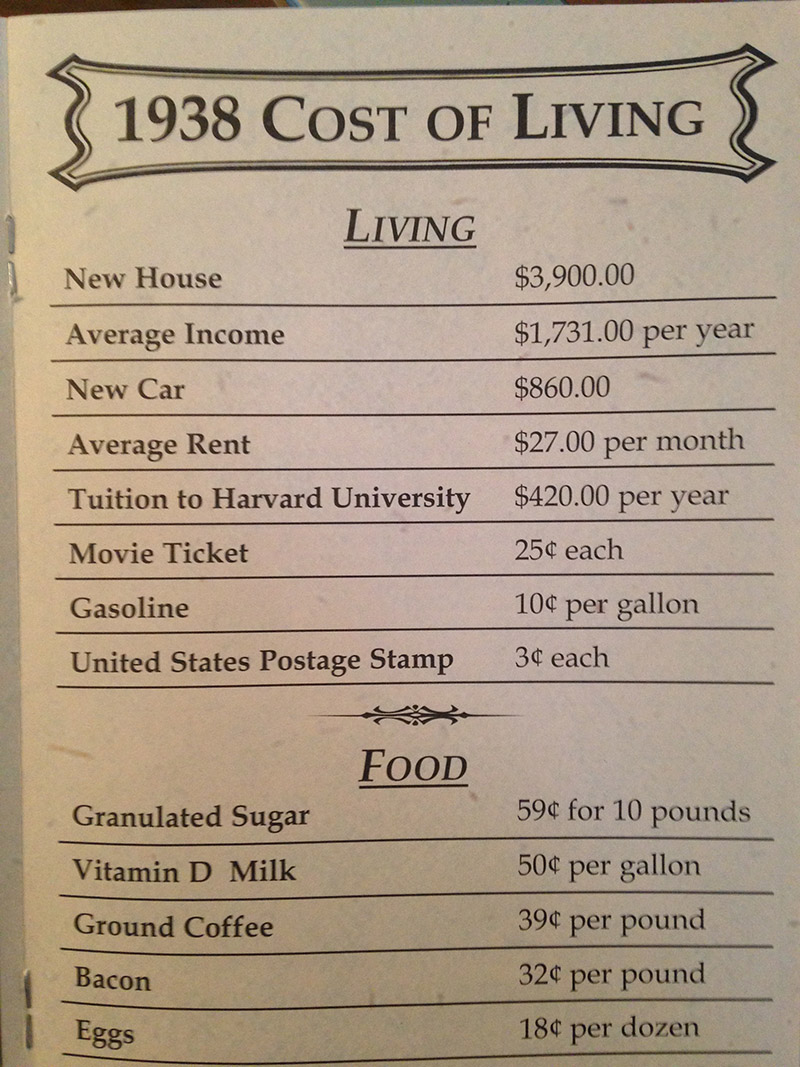

The picture in question has prices for living from 1938. It includes important items like a new home, income, new car, rent, and extreme purchasing examples like tuition for Harvard:

Source: Reddit

You can normalize costs over time through adjusting for inflation. Back in 1938 a new home cost about two times the annual average income. A new car was only about one-third the cost of the annual average income. These figures are important because back in 1938, using credit was only a small factor in purchasing goods. The middle class didn’t start blossoming until after World War II so you would expect that things were still tough for regular households. What we find though is that compared to the typical income, buying a new home or buying a car was relatively doable for most households.

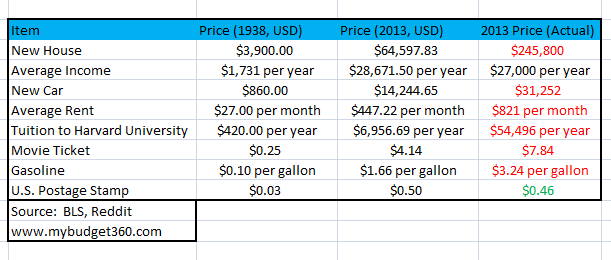

Now adjusting all these figures for inflation shows how much more expensive things have become and how dependent we now are to financing purchases with debt (created by the banking system):

This chart shows the impact of inflation and the declining purchasing power of the US dollar. For example, a new home adjusting for inflation (using the BLS calculator) should cost around $64,597 per year. The current cost of a new home? $245,800. The average income has stayed about the same normalizing for inflation (doesn’t say much since we are going back to the Great Depression here). A new home today costs nearly 10 times the annual average income of a worker. The two income trap has largely hidden this inflation since it now takes two households to accomplish what one income was able to do 75 years ago. On top of that, people now need to go into massive debt just to purchase a home.

Take a look at the cost of a new car as well. In 1938 a worker was able to purchase a new car with one-third of their annual income. Today a new car is more expensive than the annual average income. This is why in 2013 one of the top growing consumer debt sectors was with automobile loans. If things stayed the same, the cost of attending Harvard for one year in 2013 would be closer to $7,000 per year (the current tuition is $54,496 per year). It isn’t only Harvard charging incredibly high tuition around the country. Of course the higher education bubble is one of the most pressing issues around creating a $1.2 trillion student debt market.

Rent, movie tickets, and even gasoline are much more expensive today adjusting for inflation. This puts a heavier strain on the pocketbook of most Americans. It also has created a dependency on debt. We do have stronger safety nets so we don’t have the “in your face” poverty of the Great Depression. Yet we still have close to 48 million Americans on food stamps. The area that has seen prices become more affordable is with food. This however is largely derived from better access to food and products and the mass production of this commodity. Yet the bigger costs of living in housing, cars, rent, and going to college are all much more expensive today. It may feel cheaper to some if they only look at their monthly debt payment but the true costs have increased.

The impact of a falling dollar

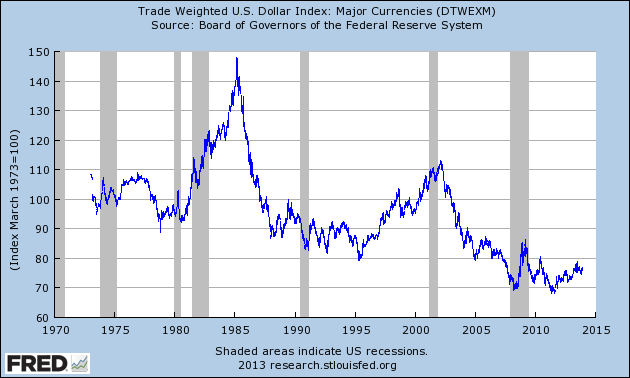

The trend of the US dollar is pretty clear since the Federal Reserve took the helm of the ship:

Without a doubt, life has gotten better since 1938 in terms of healthcare, technology, cars, sanitation, and overall quality of life. Yet this may be a false comparison argument assuming that this only came about because of the Fed. Quality of life had already started improving before this as well via the Industrial Revolution and these things were happening regardless of the money system. What this current debt based system has created is a massive increase in the price of goods through long-term financing. Should people only have the ability to go to college if they assume mountains of debt? For the average worker this may be the only road.

The US dollar even in the past few decades has taken a big hit:

Why does it feel like things are more expensive? Because they are. You may not feel the impact of inflation in one year but over time, it has a dramatic and obvious effect. The fact that the Fed now has $4 trillion on their balance sheet and continues this QE experiment reflects an addiction to easy debt. The addiction now truly benefits a very small segment of our society and that is why inequality is worse today than it was in 1938. It should tell you something where regular purchases from 1938 are now only feasible by going into massive debt.

This is a MUST READ article on the impact of our soaring non-asset money-based national debt and its impact on inflation.

Influential economists and business leaders, as well as political leaders, should read Harold Moulton’s The Formation Of Capital, in which he argues that it makes no sense to finance new productive capital out of past savings. Instead, economic growth should be financed out of future earnings (savings), and provide that every citizen become an owner. The Federal Reserve, which has been largely responsible for the powerlessness of most American citizens, should set an example for all the central banks in the world. Chairman Benjamin Bernanke and other members of the Federal Reserve need to wake-up and implement Section 13 paragraph 2, which directs the Federal Reserve to create credit for local banks to make loans where there isn’t enough savings in the system to finance economic growth. We should not destroy the Federal Reserve or make it a political extension of the Treasury Department, but instead reform it so that the American citizens in each of the 12 Federal Reserve Regions become the owners. The result will be that money power will flow from the bottom up, not from the top down––not for consumer credit, not for credit that doesn’t pay for itself or non-productive uses of credit, but for credit for productive uses to expand the economy’s rate of growth.

The following is based on a presentation by Norman Kurland, President of the Center for Economic and Social Justice (www.cesj.org)

We need policies that will expand the rate of private sector growth through Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) and other credit democratization vehicles. The Federal Reserve discount mechanism under section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act needs to be refined. The aim should be to radically reduce the cost of capital credit to enable workers and citizens generally to gain equity shares and dividend incomes from the process of financing growth capital, without the use of tax subsidies. It should also reduce the reliance on tax incentives and subsidies for financing expanded ownership, as part of a more comprehensive national economic empowerment strategy of “capital homesteading.”

The discount mechanism of the Federal Reserve (section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913) should be reactivated, with appropriate modifications and safeguards, to allow qualified banks and financial institutions to discount “eligible” industrial, commercial, and agricultural paper, representing production-oriented loans to leveraged ESOPs, IRAs, community investment corporations, and similar mechanisms for securing access to low-cost capital credit for broadening capital ownership among workers, area residents, and other non-affluent citizens.

When the Federal Reserve Act was passed, Congress intended the purchase of “eligible paper” to be the main way that the Federal Reserve System would create bank reserves. When this practice was followed, the banks in a particular area could obtain loanable funds in direct proportion to the community’s needs for money. But in recent years, the Federal Reserve has purchased almost no eligible paper.

When the Federal Reserve System was set up in 1914 the money supply was expected to grow with the needs of the economy. It was hoped that by monetizing “eligible” short-term commercial paper, by providing liquidity to sound banks in periods of stress, and by restraining excessive credit expansion, the banking system could be guided automatically toward the provision of an adequate and stable money supply to meet the needs of industry and commerce. To safeguard their liquidity and provide a base for expansion, the member banks could obtain credit from the nearest Federal Reserve bank, usually by rediscounting their “eligible paper” at the bank-i.e. selling to the Reserve Bank certain loan paper representing loans which the member bank had made to its own customers (the requirements for eligibility being defined by law). If necessary, the member banks might also obtain reserves by getting “advances” from the Federal Reserve bank.

In other words, under a standard central banking system, businesses or other productive enterprises would obtain loans at their local commercial bank. The commercial bank, in a process known as “discounting,” would then sell the qualified loan paper of the business enterprises to the central bank. In the case of the United States, the commercial bank would sell its paper to one of the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks. To be able to purchase the “qualified paper,” the Federal Reserve would either print new currency or simply create new demand deposits.

As originally intended when the Federal Reserve System was established, this process would create an asset-backed currency that increased as the need for money increased, preventing deflation. As the loans were repaid, the currency would be taken out of circulation, or the demand deposits “erased” from the books. This would remove money from the economy that was not linked directly to hard assets, and would thus prevent inflation.

Although no actual teller’s window exists where commercial banks stand in line to sell loan paper to the Federal Reserve, the transaction is described as taking place at “the discount window.” When the “discount window” is “open,” commercial banks can sell their “qualified industrial, commercial and agricultural paper” to the central bank. When the “discount window” is “closed,” commercial banks must go elsewhere to obtain excess reserves to lend, or cease making loans.

How Has The Discount Mechanism Been Used?

Despite the fact that the discounting mechanism was intended under the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 to be the main means for controlling the American money supply, it has long been abandoned as an integral part of the United States financial system. The discount window has been used to help bail out a few companies or countries considered “too big” or too important to fail. Overall, however, the money creation powers of the Federal Reserve have been used to monetize government debt. Since this is not how the system was designed to operate, a number of problems have resulted.

Our economic problems are usually blamed on decisions by Congress or the President, particularly those decisions that result in nonproductive or counterproductive spending and tax policies. Little is said about decisions by the Federal Reserve, many of which, as binary economist Louis Kelso and others have pointed out for over 40 years, have been equally counterproductive. Fed policies have added to the problem of government deficits, fueling the growth of the national debt to today’s level of double-digit trillions (making the United States the highest government debtor in the world). This has artificially and unnecessarily slowed the growth rate of the private sector.

As a result, what Kelso and other ESOP pioneers predicted is becoming increasingly evident:

• Continuing economic disenfranchisement of the American people.

• Low rates of peacetime economic growth.

• Rates of private sector investment far below U.S. potential.

• Excessive use of nonproductive credit in the public and private sectors.

• Downsizing of U.S. companies in competition with foreign companies with lower labor costs.

• Mounting trade deficits in the global marketplace.

• A growing gap in consumption incomes between the wealthiest Americans and ordinary workers and the poor.

• Under-use of human talent and new technologies that could be employed to improve America’s competitiveness in the global marketplace.

The reforms of the Federal Reserve Act proposed would be fully consistent with its original purposes––to provide an adequate and stable currency and foster private sector growth. These reforms would allow our country to take full advantage of the immense potential of a properly designed central banking system. They would restore a more healthy balance between Main Street and Wall Street, and between the non-rich and the already rich. The proposed reforms would shift the focus of the Federal Reserve from support of public sector growth and indifference to non-productive uses of credit, to support of more vigorous private sector growth, the favoring of productive uses of credit, and broadened citizen access to capital credit.

Most important, the proposed new boost to expanded capital ownership for private sector workers and other citizens would not be constrained by Federal Reserve balanced budget restrictions. It would involve no new “tax expenditures” or subsidies. Nor would it rely on existing pools of domestic or foreign wealth accumulations. It would be “A Proposal to Free Economic Growth From the Slavery of [Past] Savings”––a shift to what Kelso called “pure credit.”

For the complete article see The Federal Reserve Discount Window at http://foreconomicjustice.org/?p=1508.

http://www.mybudget360.com/cost-of-living-1938-to-2013-inflation-history-cost-of-goods-inflation/