(Britta Pedersen/dpa Picture-Alliance/AP Images)

On August 9, 2017, David Bollier writes in The Nation:

In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s shocking election victory, a shattered Democratic Party and dazed progressives agree on at least one thing: Democrats must replace Republicans in Congress as quickly as possible. As usual, however, the quest to recapture power is focused on tactical concerns and political optics, and not on the need for the deeper conversation that the 2016 election should have provoked us to have: How can we overcome the structural pathologies of our rigged economy and toxic political culture, and galvanize new movements capable of building functional alternatives?

Since at least the 1980s, Democrats have accepted, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, the free-market “progress” narrative—the idea that constant economic growth with minimal government involvement is the only reliable way to advance freedom and improve well-being. Dependent on contributions from Wall Street, Silicon Valley, Hollywood, and Big Pharma, the Democratic Party remains incapable of recognizing our current political economy as fundamentally extractive and predatory. The party’s commitment to serious change is halfhearted, at best.

While the mainstream resistance to Trump is angry, spirited, and widespread, its implicit agenda, at least on economic matters, is more to restore a bygone liberal normalcy than to forge a new vision for the future. The impressive grassroots resistance to Trump may prove to be an ambiguous gift. While inspiring fierce mobilizations, the politicization of ordinary people, and unity among an otherwise fractious left, it has thus far failed to produce a much-needed paradigm shift in progressive thought.

This search for a new paradigm is crucial as the world grapples with some profound existential questions: Is continued economic growth compatible with efforts to address the urgent dangers of climate change? If not, what does this mean for restructuring capitalism and reorienting our lives? How can we reap the benefits of digital technologies and artificial intelligence without exacerbating unemployment, inequality, and social marginalization? And how shall we deal with the threats posed by global capital and right-wing nationalism to liberal democracy itself?

In the face of such daunting questions, most progressive political conversations still revolve around the detritus churned up by the latest news cycle. Even the most outraged opponents of the Trump administration seem to presume that the existing structures of government, law, and policy are up to the job of delivering much-needed answers. But they aren’t, they haven’t, and they won’t.

Instead of trying to reassemble the broken pieces of the old order, progressives would be better off developing a new vision more suited to our times. There are already a number of projects that dare to imagine what a fairer, eco-friendly, post-growth economy might look like. But these valuable inquiries often remain confined within progressive and intellectual circles. Perhaps more to the point, they are too often treated as thought experiments for someone else to implement. “Action causes more trouble than thought,” the artist Jenny Holzer has noted. What is needed now are bold projects that attempt to demonstrate, rather than merely conceptualize, effective solutions.

The challenges before us are not modest. But it’s now clear that the answers won’t come from Washington. Policy leadership and support at the federal level could certainly help, but bureaucracies are risk-averse, the Democratic Party has little to offer, and the president, needless to say, is clueless. It falls to the rest of us, then, to figure out a way to move forward.

The energy for serious, durable change will originate, as always, on the periphery, far from the guarded sanctums of official power and respectable opinion. Resources may be scarce at the local level, but the potential for innovation is enormous: Here one finds fewer big institutional reputations at stake, a greater openness to risk-taking, and an abundance of grassroots imagination and enthusiasm.

Beyond the Beltway’s gaze, the seeds of a new social economy are being germinated in neighborhoods and farmers’ fields, in community initiatives and on digital platforms. A variety of experimental projects, innovative organizations, and social movements are developing new types of local provisioning and self-governance systems. Aspiring to much more than another wave of incremental reform, most of these actors deliberately bypass conventional politics and policy. In piecemeal fashion, they unabashedly seek to develop the DNA for new types of postcapitalist social and economic institutions.

The “commons sector,” as I call this bricolage of projects and movements, is a world of DIY experimentation and open-source ethics that holds itself together not through coercion or profiteering but through social collaboration, resourceful creativity, and sweat equity, often with the help of digital platforms. Its fruits can be seen in cooperatives, locally rooted food systems, alternative currencies, community land trusts, and much else.

While these insurgent projects are fragmentary and do not constitute a movement in the traditional sense, they tend to share basic values and goals: production for household needs, not market profit; decision-making that is bottom-up, consensual, and decentralized; and stewardship of shared wealth for the long term. They reject the standard ideals of economic development and a return on shareholder investment, emphasizing instead community self-determination and the mutualization of benefits.

Not surprisingly, the Washington cognoscenti have evinced scant interest in these emerging forms of social economy and their political potential. As the 2016 campaigns showed, mainstream politicians can barely discuss climate change intelligently, let alone imagine a post-fossil-fuel economy (as the climate-justice and transition-towns movements do) or apply deep ecological principles and wisdom traditions to politics (as Native Americans have done at Standing Rock). They are similarly oblivious to the hacktivists developing community-driven alternatives to Uber and Airbnb, and to the work of the social-and-solidarity-economy (SSE) movement to build multi-stakeholder cooperatives for social services.

But that’s precisely why those seeking profound change should be paying attention to these experiments. The commons sector goes beyond the orthodox approach to social change and justice, which tends to privilege individual rights and the redistribution of wealth via the tax system and government programs. Instead, the animating ideals of the commons are collective emancipation and the “pre-distribution” of benefits by giving people direct ownership and control over discrete chunks of land, water, infrastructure, housing, public space, and online services.

With greater equity stakes and opportunities for self-governance, people are remarkably eager to contribute to their communities, whether local or digital. They welcome an escape from consumerism, exploitative markets, and remote bureaucracies. These sorts of local and regional experiments not only advance effective structural solutions at a time when national politics is dysfunctional; they also provide meaningful ways for ordinary people to become agents of change themselves.

Almost 50 years ago, Fannie Lou Hamer came up with a shrewd strategy for dealing with community disempowerment—in her case, the vestiges of the plantation system and exploitative white-owned businesses. The civil-rights leader purchased hundreds of acres of Mississippi Delta farmland so that poor blacks could grow their own food. “When you’ve got 400 quarts of greens and gumbo soup for the winter, nobody can push you around or tell you what to say or do,” Hamer noted.

This is roughly the same strategy that must be pursued today. Relocalizing and decommodifying production and services represents a compelling strategy for the small cities, towns, and rural areas that have been ruthlessly hollowed out by big-box stores, online retailers, automation, big agriculture, and outsourcing.

In fact, that’s just what the local-food movement has done over the past few decades. Faced with a long list of agribusiness horrors—pesticides, processed foods, monoculture farming, seed monopolies, a loss of biodiversity, and more—countless champions of localism retrenched to create a semi-autonomous parallel economy on their own terms: community-oriented, fair-minded, humane, and ecologically respectful. Today, there are more than 1,650 community-supported agriculture (CSA) projects and more than 8,000 local farmers’ markets across the country. Organic farming is a robust market sector, and agroecology and permaculture are pointing the way to eco-friendly approaches.

In California, the Food Commons Fresno project is one of the most ambitious regional efforts to reimagine the food system from farm to plate. Even though Fresno is located in the heart of prime agriculture lands, the region has been ecologically abused for decades and is a food desert for half a million low-income residents and farm workers. To develop systemic solutions, the Food Commons has established a network of community-owned trusts that bring together landowners, farmers, food processors, distributors, retailers, and workers to support a shared mission: high-quality, safe, locally grown food that everyone can afford.

Instead of siphoning away profits to investors, the Food Commons mutualizes financial surpluses on a system-wide scale, reducing market pressures to deplete the soil, exploit farm workers, degrade food quality, and raise prices. This approach, writes the social thinker John Thackara, “marks a radical shift from a narrow focus on the production of food on its own, towards a whole-system approach in which the interests of farm communities and local people, the land, watersheds and biodiversity are all considered together.”

Another impressive innovation in regional self-determination is the BerkShares currency, launched in 2006 by the Schumacher Center for a New Economics (where I work) in the largely rural Berkshires of western Massachusetts. The goal is to strengthen the local economy and community life by reengineering the flow of money. Anyone can exchange $100 in US currency for $105 worth of BerkShares at any of four banks with a total of 16 branches throughout Berkshire County, and then spend them at 400 participating businesses. Consumers get a 5 percent bump in purchasing power from this buy-local strategy while boosting the regional economy and strengthening the region’s identity. The BerkShares story is part of a global trend in which dozens of localities worldwide are deploying their own currencies to reclaim some measure of control from hedge funds and banks.

New-economy renegades are not shy about engaging with the policy world, but many regard it as a rigged game that won’t yield the transformations needed. In the meantime, they ask, why not grow our own greens and make our own gumbo soup? As in Fannie Lou Hamer’s day, the focus should be on securing tangible results and greater leverage for change.

Relocalization strategies can also help reinvigorate democratic self-governance. Just as the rise of public-interest organizations in the 1970s propelled far-reaching changes, today our economic future is taking shape in new organizational forms. Innovative cooperative structures, pool-and-share projects, self-managed digital platforms, and collaborative global networks are changing the topography for pursuing social change.

One of the most notable new forms may be the platform cooperative, a socially constructive alternative to Silicon Valley start-ups, which famously like to “move fast and break things.” Gig-economy companies rely on heaps of capital, proprietary algorithms, and political muscle to control new markets that leapfrog over government standards for public safety, fair labor, and consumer protection. Platform co-ops are attempting to write a different story: Instead of using networking technologies to extract money from communities for the benefit of investors and speculators, platform co-ops work with communities, workers, and consumers to share the gains.

These dynamics play out at Stocksy United, a global co-op of photographers that sells royalty-free stock photos and video, and on service-swapping platforms like TimeBanks, which uses a currency of hours contributed to helping people meet needs and build circles of mutual support. Another vanguard player is Enspiral, a New Zealand–based cooperative that developed the popular Loomio platform for online deliberation and decision-making. (For more on platform co-ops, see The Internet of Ownership)

When community commitment and digital platforms come together, they often give rise to “cosmo-local” production, as Michel Bauwens of the P2P Foundation calls it. This is a new model of manufacturing that allows “light” nonproprietary knowledge and design to be collaboratively produced on a global scale, while enabling “heavy” physical things to be produced locally at minimal cost. This fledgling model could greatly reduce carbon emissions and transport costs while building local economic capacity.

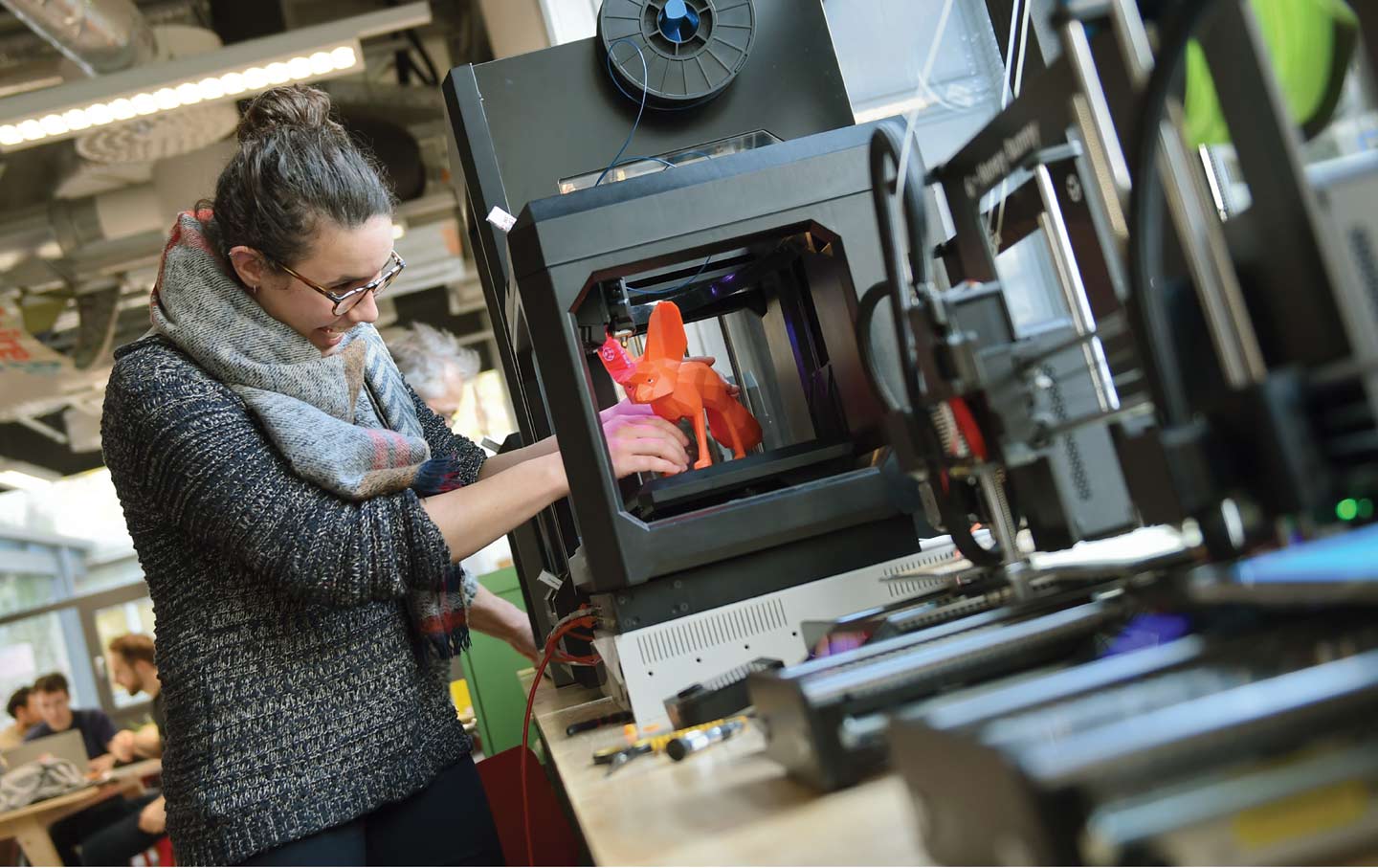

The rudiments of cosmo-local production are evident at fab labs (short for “fabrication laboratories”) and so-called hackerspaces—participatory communities of socially minded artists, designers, engineers, entrepreneurs, and techies who use computer-assisted tools to produce vanguard industrial designs. This production approach has been dubbed “SLOC”—small and local, but open and connected—a framework that scrambles the standard understanding of the economy as controlled by nation-states and corporations. SLOC integrates the local and transnational into a remarkably creative provisioning sector—commons-based peer production—that is already developing farm equipment (Farm Hack, Open Source Ecology), furniture (Open Desk), houses (WikiHouse), animated videos (Blender Institute), and cars (Wikispeed).

To conventional policy minds, altering the micro-dynamics of organizations may seem irrelevant to the task of making broadscale social change. But transforming organizational systems and cultures on a small scale may be one of the most effective ways to bring about macro-change. Just as the microprocessor and the telecommunications network changed the inner dynamics of business, eventually transforming the global economy itself, the rise of self-organized governance and networked collaboration is opening up strategic opportunities on a larger scale.

Attempting to move beyond neoliberal capitalism may sound naive. But over the past two decades, some remarkable progress has already been made. Besides a range of relocalization strategies, a new sector of commons-based peer production has revolutionized software development, scientific research, academic publishing, education, and other fields by making their outputs legally and technically shareable. In the halls of government, however, policy-makers and even progressives show little interest in the profound political and economic implications of free and open-source software, Creative Commons licenses, citizen science, data commons, open educational resources, and open design and hardware.

Most of these and other movements are seen as too small, local, unorthodox, or little-known to be consequential. They don’t swing elections. Their participants tend to eschew politics and policy, and often don’t regard their work as part of a unified movement. They see themselves as part of a pulsating pluriverse of autonomous projects, each working diligently in its own separate sphere.

Counterintuitively, this pluriverse may fuel a true progressive revival. “The next big thing will be a lot of small things,” the designer Thomas Lommée predicted recently, neatly capturing the structural logic of postcapitalist movements and the generativity of the Internet.

Acting on this insight calls for a new mind-set. Greater attention should be paid to places and players on distributed networks. The swarms of self-selected individuals and projects should be recognized as serious actors that can meet real needs in new ways. We also need to acknowledge the limits of markets and centralized bureaucracies, which are so often hell-bent on asserting total control, engineering dependencies, and eliminating the space for social deliberation and genuine human agency.

By enabling self-organized groups to bypass large institutions and formal systems of authority, and to set their own terms for establishing social trust and legitimacy, we enter the headwaters of a new kind of politics, one that is more accountable, decentralized, and human-scale. The substantive, local, and practical move to the fore, challenging the highly consolidated power structures and ideological posturing that have turned our national politics into a charade.

But, skeptics ask, can these countless small, irregular initiatives scale up? The question carries the false premise that some form of centralized management or hierarchical control is needed. As a creature of open networks and sharing, the new social economy will not be directed by a political headquarters or a federal program. That kind of control would kill it.

The participatory local economy will expand only by engaging a diverse base of American pragmatists. That just might be possible, since it offers something for everyone. As my colleague Silke Helfrich puts it: “Conservatives like the tendency of commons to promote responsibility and community; liberals are pleased with the focus on equality and basic social entitlement; libertarians like the emphasis on individual initiative; and leftists like the idea of limiting the scope of the market.”

To be sure, a constructive rapprochement with state power will have to be negotiated at some point, and in the meantime supportive laws and infrastructures would certainly help. But the success of the commons sector will hinge on the independent vitality of its projects, the integrity of its bottom-up participation, and the results it produces.

Emulation and federation—these are the means by which a new participatory sector will expand. The point is to create the conditions for grassroots initiatives to self-organize and grow. It helps to recall that the New Deal didn’t spring fully grown from the brain of Franklin D. Roosevelt, but emerged over time as the policy’s many precursors nurtured brave experiments for years. We need to plant a field of new seeds today if we are going to have anything to harvest in the years to come.

In defense of the neoliberal revolution in the 1980s, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously thundered a phrase that is often shortened to its acronym, TINA: “There is no alternative!” The result has been nearly 40 years of privatization, deregulation, austerity, and corporate governance, now reaching their farcical, destructive extremes. For those seeking to overcome this awful legacy, along with the oxymoron of “democratic capitalism,” it is time for a rejoinder: “There are plenty of alternatives!” The only question is whether the Democratic Party and mainstream progressives have any use for them.

https://www.thenation.com/article/to-find-alternatives-to-capitalism-think-small/