By Louis O. Kelso and Patricia Hetter

“The overall objective of foreign aid is to help to create conditions in the world under which free societies can survive and prosper.” (Foreign Assistance Act of 1963)

“Not so very many years ago in Iran the United States was loved and respected as no other country, and without having given a penny of aid. Now, after more than $1 billion of loans and grants, America is distrusted by most people, and hated by many.” (Abol Hassan Ebtehaj, President of Iranians Bank, Iran)

“Today, we want you to assist us to develop. We need foreign capital, we need machine tools, we need machines, we need this and we need that. You might say that we heard this before, too. You are getting a bit tired of the story. But may I put it to you like this, that we are pressing against you today as friends, and if we make good I think you will in some fashion get it back, in many ways you will get it back. If we do not make good and if, heaven forbid, we go under Communism, then we shall still press against you but not as friends.” (Mohammad Ayub Khan, President of Pakistan)

For summing up the American foreign aid program to date — its aspirations, its failure, and its challenge — these three quotations outspeak a dozen monographs.

Our foreign aid program is not helping to create conditions in the world under which free societies can survive and prosper. As presently conceived and executed, it is creating conditions that are just the opposite. Instead of winning converts to Western political institutions, it is estranging the uncommitted. Instead of impeding communism, it is preparing the way for it. Instead of furthering good will between the peoples of the recipient country and our own, it is sowing the seeds of dissension and hatred even among our friends.

Most sadly, our methods have proved incapable of penetrating the vicious circles of poverty in which the poor nations are hopelessly entrapped. Far from industrializing fast enough to support their burgeoning populations, the “emerging nations” are in fact submerging deeper into that primordial misery from which our foreign aid program so grandly hoped to lift them. In most, the per capita production of wealth is declining or at best stationary.

So far, the rich nations have treated the chronic, self-perpetuating poverty of the underdeveloped countries like a baffling pathological syndrome, prescribing, in the absence of exact diagnosis, massive shots of the standard poverty antibiotic — money — on the theory that if the patient does not survive, he would have died anyhow. About $6 billion a year now goes into these capital injections, more than half supplied by the United States. As the Wall Street Journal editorialized: “From the standpoint of the givers, it is treading the path of least resistance; if they can’t solve any basic problems, they can pretend to do so by handing out money.”

Yet we know well enough what we want foreign aid to accomplish. The difficulty is that so far the results have been the reverse of our intentions. We understand that it is the causes of poverty that have to be attacked, that we cannot alleviate its proliferating symptoms with all the riches of the West, assuming our willingness to donate them. Yet through some mysterious process, we find our resources committed to the impossible, to the neglect of the things that must be done.

We also recognize our duty and our right to use foreign aid in ways that positively encourage the poor nations to develop into free societies in the full Western sense. We know that freedom in the Western sense is absolutely inseparable from a private property, free enterprise economy. But again, as if agents of a mysterious force, we find ourselves in a race with Russia to see which of us can be the first to build socialistic or communistic economies in the poor nations.

Plans That Do Not Work

All of this irony, confusion, and failure is a consequence of our blind obeisance to methods of finance that are not suitable for industrializing the developing economies. These methods have a common flaw. Unfortunately for both ourselves and the poor nations, this flaw happens to be a cornerstone of the Puritan ethos, namely, the concept of becoming wealthy through sacrificial saving. To the Puritan, saving was not only a pleasure but a duty. That God Himself approved of frugal underconsumers could be inferred from the fact that He so regularly blessed their investments. From there it was only a short step to the next article of Puritan faith, the identification of virtue with wealth; the good man was a rich man who held his riches in stewardship and was liberal in charity and good works. In this context, poverty was a God-inflicted punishment for vice and sin.

Although the edifice of puritanism is crumbling fast, this cornerstone is as yet unchipped. Most of us with credit cards in our pockets and margin accounts at our brokers have puritan thrift in our souls — even though we know that this “virtue,” taken seriously, would quickly destroy a modern industrial economy.

Our puritan reverence for saving, in theory at least, keeps us from devising financial techniques that could industrialize the developing economies. Conventional financial methods depend exclusively on accumulated savings, that is, financial capital. Obviously, if the underdeveloped economies had savings accumulations to any significant extent, they would not be poor. What small savings they do have are owned by a microscopic portion of the population; many of these owners, not oblivious to the political instability of a poor nation in a potentially affluent world, transfer their wealth to countries that are safer.

Conventional Aid Techniques

To the poor nations, pressed by the aspirations of their impoverished masses, the West offers only three alternatives: foreign capital, as loan or investment; foreign charity, that is, so-called foreign aid; or financing through domestic capital owned by their own wealthy few. For the broad masses, as we shall see, all of these avenues end in frustration because capital produces affluence, while labor produces only subsistence.

This basic economic truth, which automation is now painfully teaching the West, explains why foreign investment eventually becomes intolerable to the host country. It leads to foreign ownership. It cannot provide affluence to the masses because affluence, the product of capital, is exported to the foreign owners or accumulated for foreign account. True, foreign-owned enterprise, like any other enterprise, creates some jobs and some jobs are better than none. But the mutual political objective of both the rich nations and the poor nations is to make the poor nations richer, not merely to provide some of their citizens with subsistence toil and make the business firms of the rich nations richer.

Use of domestic capital, to the extent that there is any, has exactly the same consequence as foreign ownership, with one difference. Affluence is not necessarily exported. It concentrates in the hands of the people who already own capital — no more than one-half of one percent of the total population in any of the developing economies. This elite cannot generally increase its already maximum consumption, nor could it solve the poverty problem by doing so. Some jobs are, of course, a by-product of this financing process, providing a negligible fraction of the masses with work opportunities. But subsistence is no substitute for affluence. As the rich grow richer and the poor poorer, an endemic process in the underdeveloped countries, the social tensions leading to political violence move inevitably toward eruption.

Government loans to private enterprise in the developing economies have the same effect as use of concentrated domestic capital. This is true because they simply further concentrate the capital ownership of the people who presently own the poor nations’ productive capital.

Myth has it that all of these tired techniques are good because they create jobs. “Say a Mass, then, Father, for the success of the new sugar mill. It will provide work for your parishioners,” says the American businessman to the Venezuelan priest. The fact is that the new sugar mill — a golden goose for its capital owners — will provide a few jobs for the priest’s parishioners. And the fewer jobs it provides, the greater success it is because the logic of technology is not to make work but to save it.

Industrialization of a primitive economy in mid-twentieth century is not analogous to the Western industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A steel mill, power plant, or factory introduced into an underdeveloped economy is already in an advanced stage of technological sophistication; its potential for providing mass drudgery has been systematically eliminated. For example, it was a great event for America when telephone lines finally connected the Atlantic Coast with the Pacific, and people on both coasts with everyone in between. This feat required an enormous amount of the most exhausting physical labor — armies of workers chopping, digging, trenching, and blasting their way across a continent. Today all that is required is a string of relay stations, which can be put up by a handful of skilled men using helicopters and other highly productive machines.

In the age of automation, the huge unskilled labor force of a poor nation is not a resource but a liability. Unless the price of labor is artificially elevated by legislation and coercive bargaining to many times its competitive market value, even full employment merely dooms labor to subsistence toil.

Government-to-government aid, either as loan or outright gift, creates state-owned enterprise in the recipient country and has a second effect of which we are uncomfortably aware. Abol Hassan Ebtehaj, President and Chairman of the Iranians Bank, Iran, told us the truth as bluntly as we are ever likely to hear it. Speaking at a San Francisco conference in 1961, he said: “Bilateral aid poisons the relationship between nations, frustrates the donor, and causes revulsion in the recipient.”

There is no reason to believe that government-owned enterprise built by multilateral aid would be less socialistic than government-owned enterprise built by bilateral aid. The most to be said in favor of the former is that it would presumably direct the hatred of the recipient country toward many nations instead of one. The choice, if there is one, is between charity dispensed in the old-fashioned basket or by modern welfare check.

The Totalitarian Approach

We may conclude that foreign aid in its present form cannot possibly contribute to stable democratic governments. Frustrated by their own ruling classes, goaded by their impatient masses, their problems only aggravated by misguided foreign help, the political leaders of the poor nations can hardly be blamed for coming to believe at last that affluence for them can only be achieved by totalitarian means and that freedom is a luxury a poor nation cannot afford.

The totalitarian approach, after all, has its advantages. By fusing ownership of land and other capital with political power, it creates a central authority strong enough to force raw materials, land, and manpower into the priorities of industrialization. Totalitarian power can enforce austerity on the affluent few and hinder them from exporting their money; it provides a deceptive ideology around which energies can mobilize, and it may convince a desperate nation that it is able to bring about industrialization faster than could insufficient or irresponsible private savings.

But these short-term advantages are bought at the price of freedom; the totalitarian approach forecloses any hope of democratic institutions. It also deliberately frustrates the acquisitive instinct — the instinct to own property rights in farms, factories, and productive assets generally. To the extent that it increases the number of jobs, it has some incentive effect, but the property-acquisition incentive, which so spectacularly powered the industrial revolution in the West, is methodically suppressed and discouraged.

While the strength of totalitarian ideology springs largely from its promise to eliminate the evils of concentrated ownership, in practice it simply replaces one form of concentration with another. And it lays the foundation of a virtually unsolvable future dilemma, the same dilemma now afflicting our own economy, in which labor is erroneously recognized as the primary factor in production, thus setting the stage for total confusion as automation eliminates the usefulness of an expanding portion of the labor force.

The Savings Method

When the developing nations look to the industrialized nations of the West for delivery from their impasse, we can only counsel the austere principle that worked for us — save now, consume later. But puritan virtues cannot be imposed from without; besides, our ancestors, living in a world where nearly everyone was poor, were not tempted by the luxuries of their neighbors. Poverty was easier to bear before a flourishing technology offered liberation.

During our own industrial revolution, the limitations to economic growth were mainly technological. Thus we did not feel the pinch of financing new productive enterprises exclusively from slowly hoarded savings. In their rush to industrialize, the developing economies want only our latest technology. They also want — and properly suspect they can get — a sound correlation between their growing industrial power and the individual power of their peoples to consume. For them, the piggy-bank approach is much too slow; the hobbles it imposes are felt immediately and painfully.

Like the totalitarian approach, the conventional savings method is only partially incentive. It harnesses the energies of those who get new jobs, as a result of new industry, and the acquisitive instincts of those few who can save and whose savings are used to finance new capital formation. But it is disincentive for the masses for whom capital ownership is forever beyond reach.

Something else can be said for the savings method. It does create a free enterprise, private property economy — for awhile. But capital is the main producer of wealth in an industrial economy, and ownership of new capital automatically goes to the people whose money has been used to finance it. These people are, of course, the already wealthy. Although total concentration of political and economic power is avoided, ownership of economic power necessarily is forced to concentrate in the hands of a stationary — or even shrinking — proportion of the population.

As industrialization advances, this process continues in an accelerating spiral. Consumption, which is left to chance, cannot keep up with production, which is systematically expanded. Finally, forced redistribution of income is compelled in order to restore a semblance of balance. And after a series of these operations, where principle is cut away by expediency, what remains is only the hollow shell of a private property economy. As the lawyer-economist Adolf A. Berle, Jr., has put it: “The capital is there; and so is capitalism. The waning factor is the capitalist.”

Concentration of economic power is the evil spectre of capitalism, which still haunts the Western economies. It is an evil inherent in the technique of financing new capital formation exclusively out of savings. It is the inner flaw that eventually destroys the private property economy it has created and with it the entire superstructure of individual liberties and rights.

Totalitarianism now, or countless more years of wretched poverty as down payment on a private property, free enterprise society that will have to be socialized later — it is a dismal choice. If we step boldly up to this dilemma and inspect its horns, we shall discover that they are the horns of a sacred cow. The savings theory, far from being an immutable absolute, is merely an old and deeply ingrained business custom, a technique for organizing the people and things that are to take part in forming the new capital.

Everyone knows that money, that is, savings, does not enter directly into the physical construction of things like new steel mills. In one sense only are savings indispensable to their creation; the physical plant and equipment are designed to produce steel; they are not used, or suitable for being used, eaten, or worn, or to immediately satisfy any other human want. And since these specialized objects are owned by someone, they become, in a physical sense, savings in the hands of the owner. Since he can sell them at will, or pledge them to secure loans, they may be regarded as the equivalent of the money they would bring if pledged or sold. Similarly, since money can readily be converted into money, the distinction between financial capital and physical capital can often be disregarded.

Moreover, while the new steel mill is still in the prospectus stage, a body of experts has pronounced it economically feasible. By definition, these experts are people whose judgment is accepted by banks, suppliers of equipment, and others who stand to gain or lose by accepting the experts’ judgment. What the experts mean by “economically feasible” is that they expect the new steel mill, after paying its current operating costs, not only to produce wealth equivalent to its costs of capital formation but a hundred or thousand times that figure. And if the new enterprise is soundly conceived and well managed, this is generally what it does.

Now we see the real function of savings in the building of new physical capital. Stripped of its hoary mystique, savings, or money, or financial capital is simply insurance. The money subscribed for investment in a new enterprise merely ensures that the factory, ship, railroad, or other newly formed capital will produce income sufficient to defray the costs of its formation and that the income will be so applied.

A Plan That Would Work

Once we have torn off the blindfold of convention and seen that the use of savings in the new capital formation process is simply a form of insurance, we understand that the poor nations desperately and urgently need a second and supplementary financing technique that does not depend on past savings. Such a technique — by treating an insurance problem in an insurance manner — could enable the developing economies to organize new capital formation in such a way that the goods and services involved could be paid for out of the wealth produced by the newly formed capital.

Nor is there any theoretical or practical reason for not spreading the insurance risk by imposing premiums upon the new equity owners, who would be credit financed in a manner that would bring about a rapidly growing ownership base. In effect, the developing economies using this method would be able to finance much of their industrialization through future savings owned by households that previously were without capital.

Such a technique, built into a rational plan, could launch the underdeveloped economies on an industrialization breakthrough beyond the scope of imagination — Western or Communist. Even more momentous, the industrial revolutions powered by this technique would be enormously superior to our own. They would reveal capitalism purified of its internal flaw imposed by the total domination of the savings technique that compels unlimited concentration of capital ownership and economic power in the Western nations.

In other words, by severing the rigid historic linkage between new capital formation and past savings, it would at last be possible to generate capital ownership broadly throughout a population, building for political democracy its only possible economic support and, for the first time in the history of capitalism, synchronizing the industrial power to produce with the economic power to consume.

We can better understand the plan by taking inventory of our assets. The underdeveloped countries have land, trainable manpower, and natural resources, at least some. The industrial nations have technology, including talent and experience in industry, commerce, engineering, and science. They also have the machinery and equipment needed by the underdeveloped nations until their own capital goods industries are built. The owners of all these ingredients must be induced to contribute them at the proper time and in the required combinations and amounts, to build or expand productive enterprises in the developing economies while payments for these contributions, and of interest on credit, must be deferred until the enterprise is producing the income for these payments.

As these various resources are being organized into corporate structures capable of channelling their net incomes into the deferred payments, we must devise ways of getting ownership of these corporations into the hands of a growing number of families in the developing economies who previously have owned little or no capital. Through these steps, future savings, that is, future capital ownership, will begin to be created in the form of individually owned equity securities of the new or expanded enterprises that have paid from their operations the costs of their new capital formation.

These “paid-up” enterprises must then be required to pay out most, if not all, of their net incomes to their growing bodies of stockholders. Through this measure, the purchasing power produced by capital, as well as the purchasing power produced by labor, will support the economic power of the masses to consume. Methods of financing expansion from future savings must be always available to such enterprises so that they will not have to withhold purchasing power from their stockholders for this purpose.

As for the actual techniques, we see at once that we already have them. The following procedure is only one of several that might be employed. It involves methods already widely used and well understood in other areas of finance. The possibility that the new enterprise might fail to produce its costs, or make the deferred payments, could be insured against by creating an agency similar in function to the Federal Housing Insurance Agency. With or without such an agency, capital stock equal in par or stated value to the required capital costs could be sold, on a nonrecourse basis, to new stockholders chosen from families previously incapable of acquiring capital ownership.

Under loans that might or might not be guaranteed by the corporation being financed, commercial banks could loan the new stockholders the purchase price. Medium-sized portfolios of such stock could be held in individual escrow accounts in the financing bank until their earnings defray the purchase price and interest. The loan proceeds can go directly to the corporation to pay for new capital formation. The portfolio purchased on credit would certainly be diversified. It should contain stocks selected from a number of enterprises that have been financed along similar lines.

In the hands of the banks making stock purchase loans, the loan paper should be discountable with the central bank or the development bank of the developing economy. For an insuring fee, U.S. or international financing agencies might indemnify the rediscount bank and provide currency exchange arrangements for the mutual benefit of the developing economy and U.S. or European capital goods suppliers.

Xlandia’s Experience

A simplified but realistic example illustrates the technique. A developing economy — call it Xlandia — seeks to materially improve its economic condition by expanding its production of food and fiber, both for consumption and for export. A key factor in increasing its agricultural output is the construction of facilities for the production of nitrogenous fertilizers, including basic anhydrous ammonia, aqua ammonia, ammonium sulphate, and the usual liquid and dry mixes containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur compounds. Building such a chemical complex in Xlandia, supplying it with raw materials, and operating it are technically feasible.

Study shows that the largest plant that can be profitably operated at the outset would cost $10 million, complete with sufficient distribution equipment, storage facilities at the plant and at other locations in the market area, also including financing, organizational, and start-up expenses. An average annual net return of 20 percent after depreciation and taxes would be extremely modest in many locations justifying such enterprises.

After careful study, it is determined that a fertilizer corporation, Agroboost, Inc. will be financed entirely through the issuance of shares of $100 par value capital stock, and that personal capital acquisition loans will be made to families meeting certain qualifications to enable the purchase of forty shares per family. For purely psychological reasons, a down payment of five percent or $200 is imposed. At this point the details of what the qualifications should be, in addition to the five percent down payment, are unimportant except that they should encourage socially desirable attributes such as education, skills, business or public service, experience, and the like, and should exclude already affluent families. The objective of such a program is not to encourage greed but to make affluence accessible to those not presently possessing it. The officers and employees of Agroboost, Inc. might well be given priority in such eligibility.

Thus 2,500 families would be able to arrange through their local commercial bank nonrecourse loans of $3,800, the proceeds of which, together with the $200 down payment, would be deposited in individual escrow accounts in the name of each new stockholder. The fiduciary handling the escrow account should be either the equivalent of the trust department of a commercial bank where the trust officer, over the life of the loan, would have first-hand opportunity to explain to the new stockholder the nature and significance of stock ownership, the importance of using only the income and not the principal for consumption when the escrow account is closed and the loan paid off, and so forth. Thus the bank trust officer in such cases would become a teacher of elementary private property economics to a pupil who has a personal interest in the subject matter.

The proceeds of each stock acquisition loan, together with the down payment, would be used to purchase from Agroboost, Inc. forty shares of its capital stock. Since there presumably would be no lack of buyers for such securities under these conditions, elaborate underwriting arrangements would be unnecessary, and the stock might well be issued in installments over the construction period as funds are needed. In such a case, the financing loans need not begin to draw interest until the actual stock purchase is made. This procedure would also minimize the brief inflationary period between the loan and the commencement of production by the Agroboost, Inc. plant, marking the beginning of its anti-inflationary contribution to the economy that would continue for the life of the plant.

The shares so purchased would be deposited in each shareholder’s escrow account, to be held there as security for the particular loan until it is paid off. Contractual or governmental regulations or both could require Agroboost, Inc. to pay out all or at least a very high percentage of its net earnings each year and to look to further similar personal stock acquisition loan financing for future expansion. Contractual arrangements would also determine the rate of application of dividends on the stock to repayment of the loan and bank interest, which can be assumed to be a desirably low administered rate of, say, four percent.

This arrangement might apply all of the portfolio income on the interest and principal of the loan until the principal has been reduced to $3,000 and thereafter permit 25 percent of the dividends to flow into the owner’s hands and 75 percent to be applied on the loan account. When the loan balance has been reduced to $2,000, the division might be 50 percent to the loan account and 50 percent to the stockholder. While such an arrangement does extend the stock acquisition financing period, it also serves the basic economic purpose of accelerating the buildup of the economic power of stockholding families to consume. It must be kept in mind that this is as important as the building of the industrial power to produce, in this case, chemical fertilizers.

Depending on the extent to which dividends on the stock of Agroboost, Inc. are permitted to be paid to the stockholder prior to full discharge of the financing loan, the principal and interest loan in this instance might be fully discharged out of dividends in a period of six to eight years. If Agroboost’s net income were higher than here assumed — and it could generally be expected to be higher — the loan amortization period could be even shorter.

Ideally, the loan paper in the hands of commercial banks that made the stock acquisition loans should be discountable at a low rate with the Xlandia Central Bank. This is the essence of the technique of monetizing new capital formation.

Further desirable refinements may be added to the system, including the establishment of an FHA-like insurance agency (which we might call the Capital Generation Insurance Corporation or CGIC), which would set uniform and comprehensive feasibility testing standards to be met by corporations seeking to qualify for such financing. For a fee charged against each loan account, CGIC would insure the lending bank against loss through failure of the financed portfolio to pay its acquisition costs. If greater leverage were desired in the capital stock of Agroboost, Inc., a portion of the $10 million initial capitalization might be produced by term commercial loan, which might similarly be discountable and insurable.

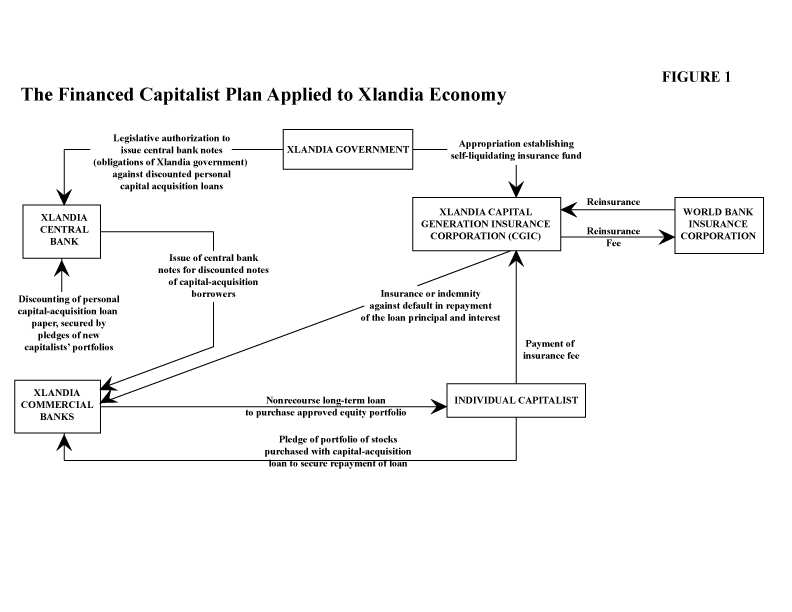

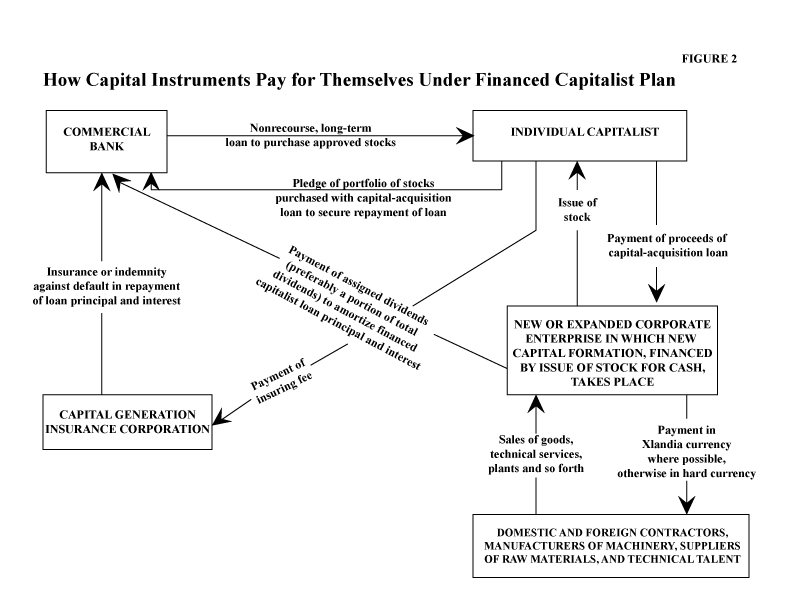

In this simplified example, we have considered only the stock of a single corporation. Good financing and investment practice would lead the financing banks under this plan, and also the insuring agency if one is employed, to insist upon diversification of each financed portfolio. Each should contain a balanced selection of stocks issued by corporations seeking new capital formation that have satisfactorily met governmentally supervised feasibility tests in addition to the requirements of each particular commercial bank that makes personal capital acquisition loans. Such feasibility test would be nothing but a reflection of good management judgment that the stocks approved would “throw off” their acquisition financing costs within an acceptable period. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the arrangement.

Effecting the Plan

Finally, who is to supply the organizational impetus for putting this technique to work in the poor nation? International entrepreneurial companies especially organized for the purpose could be the answer. The rich nations could easily organize such companies by the dozens if the industrialization of the developing economies were treated as a mutual undertaking for mutual profit, in other words, as a business partnership between enterprises of the developed country and those of the developing one. Each entrepreneurial company would commit itself, by private or governmental contract or both, to maintain its sponsored project corporations in the developing economy not in perpetuity, as foreign companies now do until they are nationalized, but for a specified length of time, for specific accomplishments, in return for a reasonable profit. The firm would arrange temporary operating contracts with experienced firms in the industrialized countries and transfer technological know-how to citizens of the developing economy. At the end of the booster stage, the firm would sell its equity in its project corporations through secondary reoffering of shares to local households who have little or no capital, using the insured bank-financed method of effecting purchase of the shares.

This plan is in the spirit of the Puritan ethos; in fact, it conserves and renews it by placing its chief virtue, thrift, in a new and workable context. Capital ownership is acquired by the individual through his savings — his investment in lieu of consumption. But this time, the income produced by his newly acquired equity capital is saved and applied in repayment of the credit extended to him to purchase stocks.

Aside from its main attraction, namely, that it would work, this financing method is free of all taint of charity. It does not concentrate ownership of new affluence-producing capital in the hands of a tiny class. It does not create or promote communistic or socialistic enterprise. It is efficient. It is aimed at the proper economic target: the causes of poverty. It creates the conditions under which free institutions can take root and grow; it provides progressively larger numbers of the broad masses with the opportunity, through capital ownership, to produce and enjoy affluence, not merely to engage in subsistence toil.

These social blessings will spring naturally from an economy that practices the first principle of economic symmetry: building the economic power to consume simultaneously with the industrial power to produce.

One could marshal an army of facts and quote a legion of observers and prophets to prove that unless we apply new concepts to the problems of the underdeveloped countries, and apply them soon, we are speeding toward disaster. But it is one thing to cry for new concepts and another to have the courage to recognize them and to try them.

It is easy to deplore the spectacle of a poor native scratching at the soil with a pointed stick and ignoring the shiny new ploughshare at his feet. But not only the technologically unsophisticated are thralls of the past. The blind spot that prefers the ancestral stick to the unknown potential of the plough is the same human blind spot that keeps us devoted to outmoded methods of finance and oblivious to the powerful new techniques we have in our hands.

We can, if we choose, lead the poor nations of the world to freedom and affluence; or we can go on giving them the stone of foreign aid instead of teaching them how to produce their own bread.

— Originally published in BUSINESS HORIZONS, Fall, 1964