On August 23, 2016, Peter Dizzies writes on MIT Technology Review:

Until recently, most prominent economists saw international trade agreements as an unequivocally good thing. Trade deals, their thinking went, boosted GDP, brought consumers cheaper imported goods, and created only modest problems for American workers, who could find new jobs if their old firms failed in the face of low-wage foreign competition.

David Autor is helping to change that thinking. Autor, Ford Professor of Economics and associate head of the economics department, has produced a series of studies over the last several years showing that trade produces clear winners and losers. The winners include U.S. companies that can manufacture goods more cheaply, as well as tens of millions of American consumers who can buy some products for slightly less money. The losers are the workers who have watched their livelihoods disappear as their regions have been devastated by the departure of manufacturing jobs.

Moreover, Autor has found, the effects of trade have been concentrated in the last 15 years or so. That’s because trade with China—formalized after that country joined the World Trade Organization in 2001—has had a far greater impact than, say, the increased trade with Mexico that occurred after the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994.

Most recently, Autor has argued that resentment over the ill effects of trade is helping to transform American politics. In areas hard hit by job losses caused by trade with China, he and his collaborators found in a new study, unhappy voters have since 2002 been electing “more extreme legislators, especially on the right,” exacerbating the polarization that has made Congress so dysfunctional. In areas dominated by non-Hispanic white voters, conservative Republicans and Tea Party candidates have made huge gains, replacing moderate Republicans and some Democrats, while districts in which people of color constitute the majority have swung further to the left.

“The politics of trade have gotten much uglier, because the consequences have now been really noticed,” says Autor. “Some people were really directly, adversely, strongly impacted. And we were not set up institutionally to help them adjust to that. We were too much in the position of saying, ‘It’s not a big deal.’”

As much as anyone in academia, Autor has persuaded people that the social impacts of trade agreements are a big deal. In other studies, including a 2013 paper, “The China Syndrome,” he and two frequent collaborators, economists David Dorn of the University of Zurich and Gordon Hanson of the University of California, San Diego, have quantified the trade-offs. Trade with China, which has increased its manufacturing capacity enormously in a short time, has cost Americans as many as 2.4 million jobs since 1999, the three economists have found—about one million of those in manufacturing. “Trade may raise GDP,” Autor says. “But it does make some people worse off.”

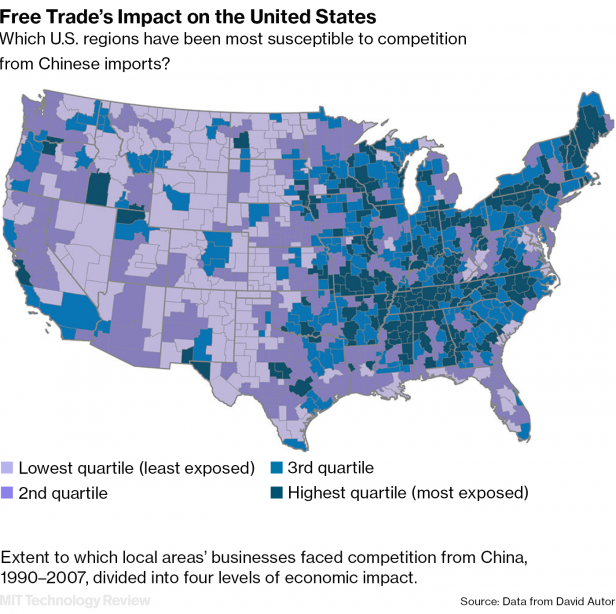

The methods Autor, Dorn, and Hanson have used to arrive at these conclusions are unique. They have closely scrutinized 722 U.S. metro areas known as “commuting zones,” looking at the shift in industrial production in areas that had been making the kinds of products China suddenly started exporting to the U.S. in the early 2000s. Through this approach, the scholars have established a new geography of trade effects. Imports from China have hit hard in former textile centers like Raleigh, North Carolina; furniture-manufacturing areas, including Tennessee; and many places that formerly manufactured shoes, leather goods, and rubber products, among other goods. Ranking all 722 zones by their exposure to Chinese manufacturing, they found that in a zone around the 75th percentile, annual income per adult dropped $549 more than it did in one at the 25th percentile.

As Autor is careful to point out, increased trade does increase aggregate wealth. U.S.-based companies like Apple, he notes, have grown partly because they can have their products made in China. And millions of Americans save a bit of money every year buying those phones, as well as cheap imported goods like T-shirts and assemble-it-yourself furniture. But the benefits and drawbacks of free trade are more unevenly distributed—and the magnitude of job losses more severe—than most economists and politicians previously realized.

The New York Times made the researchers’ study on trade and politics front-page news in April. Despite such attention, though, Autor is self-effacing about his work, joking that he’s had “multiple failed careers.” After starting college in the 1980s, he dropped out for a couple of years and took a job as a software developer in a hospital. He finished his undergraduate degree at Tufts in 1989, emerging with a major in psychology, an informal concentration in computer science, and a bit of ambivalence about his studies.

“I really loved the questions in psychology, but I really didn’t think the quality of the answers was very good,” Autor recollects. “I wanted to do something that combined the rigor of computer science with the public-good perspective of psychology.”

What exactly that would be, in 1989, was unclear. Driving across the country with his girlfriend after graduation, he heard a radio segment about a program called “Computers and You” at the famously liberal Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco. So Autor ended the road trip in that city, where he volunteered at Glide Memorial and wound up as education director of that very program, teaching computer skills classes to disadvantaged adults and children. “It was fabulously eye-opening, and I really got engaged in the question of how technology is affecting skills and opportunities,” he says. After a few years at Glide Memorial and similar work in South Africa, he attended graduate school in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, studying technology, the labor market, and inequality. To get his master’s degree, though, he had to pass graduate-level classes in statistics and economics.

“I had never taken any economics,” Autor says. “I literally didn’t know what it was. I thought it was just about the study of money.” Still, he recalls, “As soon as I got into the upper-level class, I thought, ‘This is the thing I’ve been looking for.’ Because this combines the rigor of the pure science with the social questions that I care so much about.”

Autor earned his PhD in 1999. His advisors steered him into the economics job market—and he felt “completely startled” when he landed a position in MIT’s heavyweight department. “It was like if you were playing baseball for the farm system, and all of a sudden you got called to the majors,” he says. But Autor was ready for the big leagues, publishing enough well-regarded papers to receive tenure by 2005. He has studied many subjects, including the relationship between technology deployment and job loss (he is not an alarmist about it) while delving into the gender gap in educational attainment, the value of temporary jobs to workers seeking long-term employment (it’s less than people think), and other topics.

A conversation with Hanson launched the research partnership about the effects of trade with China, with Dorn soon getting on board as well. Examining the effects of trade meant the economists were venturing into terrain where the profession had fixed views. “More than any other issue, economists have kind of been boosters for trade,” Autor says.

Indeed, Autor became an economist at a time when many in the field were concluding that technology, not trade, was principally responsible for costing workers jobs. But in the early 2000s, China entered the World Trade Organization, ushering in a new period of trade-based job losses. “Just as the debate closed, the facts changed,” Autor says. He adds: “We’re not criticizing the research people have done in the past … But we are saying [China’s rise] has to cause us to reëxamine the advice we give, and to think more carefully about how we quantify both the costs and benefits.”

Autor thinks protectionism would probably be disastrous. Instead, he advocates robust “trade adjustment assistance” for affected workers. This idea has been an “orphan” in policy circles, he says, adding that the current federal program is “stingy.” Displaced workers need training to get new jobs at comparable pay, but under the current system, they may disqualify themselves for such programs if they take menial jobs to pay the bills.

All told, Autor’s body of research demonstrates the same drive to do socially relevant work that he had coming out of college. For him, being a labor economist means studying the laborers, not just the labor. As he continues to study the nature of work today, he finds that he cannot ignore how strongly jobs affect people’s basic self-respect. His ongoing research is likely to amplify this: one recent working paper looks at the disintegration of two-parent households in areas jolted by trade effects. “Work is really wrapped up with identity,” he says. “Work is not just money for most people. They don’t fare as well when they don’t have a meaningful thing to apply themselves to.”

Gary Reber Comments:

“As Autor is careful to point out, increased trade does increase aggregate wealth. U.S.-based companies like Apple, he notes, have grown partly because they can have their products made in China. And millions of Americans save a bit of money every year buying those phones, as well as cheap imported goods like T-shirts and assemble-it-yourself furniture. But the benefits and drawbacks of free trade are more unevenly distributed — and the magnitude of job losses more severe — than most economists and politicians previously realized.”

Yet Autor, as with virtually all economists, ignore the reality that the increased in aggregate wealth is concentrated as ownership among a few Americans, while devastating to millions of other Americans and communities who have lost jobs and thus income to support their families.

Autor advocates robust “trade adjustment assistance” for affected workers as displaced workers need training to get new jobs at comparable pay.

But that proposal ignores the reality of the future. While there will be a growing call for more educated workers with the necessary education and training to meet the demand for the jobs of the future, given the current invisible structure of the economy, except for a relative few, the majority of the population, no matter how well educated, will not be able to find a job that pays sufficient wages or salaries to support a family or prevent a lifestyle, which is gradually being crippled by near poverty or poverty earnings. Thus, education is not the panacea, though it is critical for our future societal development. And younger, as well as older people, will increasingly find it harder and harder to secure a well-paying job –– for most, their ONLY source of income––and will find themselves dependent on taxpayer-supported government welfare, open and disguised or concealed.

It is imperative we decoupled from not only Communist China but all slave-wage labor countries and return to investing and developing the most sophisticated and technologically advance automation and “machine” manufacturing possible in the United States. At the same time the ownership of all future wealth-creating, income-producing capital asset formation must be broadly owned by EVERY child, woman and man, as individual citizens. This can be accomplished using pure, interest-free capital credit, solely repayable with the earnings of the investment, and without the requirement of past savings to purchase or to pledge as loan collateral.

For decades employment opportunity in the United States was such that the majority of people could obtain a job that could support their livelihood, though, in most cases related to a family, it eventually required the father and mother to both work, if they aspired to live a “middle-class” lifestyle. With “Free Trade” those opportunities began to disintegrate as corporations sought to seek lower-cost production taking advantage of global cheap labor rates and non-regulation, as well as lower tax rates abroad. This resulted in a chain reaction forcing more and more companies to outsource in order to stay competitive (thus the rise of Communist China, India, Mexico, and other third-world nation economies).

At the same time, tectonic shifts in the technologies of production were exponentially occurring (and continue to do so), which resulted (and continues to result) in less job opportunities as production was shifted from people making things to “machines” (the non-human factor) of technology making things. The combination of cheap global labor costs and lower, long-term-invested “machine” costs has forced the worth of labor downward, and this will continue to be the reality. Our only way to far greater prosperity, opportunity, and economic justice is to embrace technological innovation and invention and the resulting human-intelligent machines, super-automation, robotics, digital computerized operations, etc. as the primary economic engine of growth.

But significantly, unless we reform our system to empower EVERY American to acquire, via pure, interest-free insured capital credit loans, viable full-ownership holdings (and thus entitlement to full-dividend earnings) in the companies growing the economy, with the future earnings of the investments paying for the initial loan debt to acquire ownership, the concentration of ownership of ALL future productive capital will continue to be amassed by a wealthy minority ownership class. Companies will continue to globalize in search of “customers with money” or simply fail, as exponentially there will be fewer and fewer customers to support their businesses worldwide. Why, because the majority will be disconnected from the dividend income derived from the non-human means of production that is replacing the need for labor workers who earn wages and salaries, which are then used to purchase products and services.

Soon, industrial monopoly capitalism will reach its twin goals: concentration of productive capital ownership among the elite ownership class and work performed with as few labor workers and the lowest possible wages and salaries. The question to be answered is “What then?”

The transition to the non-human factor of production has been occurring for decades but is now experiencing exponential development –– the result of tectonic shifts in the technologies of production. As costs for computer-controlled machines become less than the cost of human workers, and the skills and productivity of the machines exceed those of human workers, then robot worker numbers will rapidly increase and enable our society to build architectural wonders, revitalize and redevelop our cities and build new cities of wonder and amazement, along with support energy, transport, and communications systems. Super-automation and robotics is transforming the world of manufacturing as robots become lighter, more mobile, and more flexible with better sensing, perception, decision-making, and planning and control capabilities due to advanced digital computerization. Super-automation and robotics operated by human-intelligent computerization will dramatically improve productivity and provide skills and abilities previously unique to human workers. This will effectively increase the size of the labor work force globally beyond that provided by human workers, no matter what the level of education attained. With advanced human-level artificial intelligence, computer-controlled machines will be able to learn new knowledge and skills by simply downloading software programs and apps. This means that the years of training that apply to personal human development will no longer apply to the further sophistication and operation of the machines. The result will be that productivity will soar while the need and demand for human labor will further decline. Unfortunately, in the long term, unless the vast majority of people have a substantial and viable source of income other than wages and salaries, the impact of technological innovation and invention as embodied in human-level artificial intelligence, machines, super-automation, robotics, digital computerized operations, etc. will be devastating.

There are ONLY two options: either “Own or Be Owned.” The “Owned” model is what our society practices today and is expressed as monopoly capitalism (concentrated ownership) or socialism (taxpayer-supported redistributed social benefits). The “Own” model, or what my colleagues and I term the Just Third Way, has yet to be implemented on the scale necessary to empower every man, woman, and child to acquire private, individual ownership stakes in the future income-producing productive capital assets of the “intelligent automated machine age” –– facilitated by the future earnings of their investments in the companies developing and employing this unprecedented economic power.

Unfortunately, the disruptive nature of exponential growth in technology and its impact on productivity –– tectonically shifting production of products and services from human workers to non-human means –– is not understood and ignored by the economic establishment, academia, and our political leaders.While the rate of technological progress is directly proportional to the number and quality of the people engaged in the fields of science and engineering, economic policy is the mechanism that fuels investment and development of technological innovation and invention. This is where education is critical to our future societal development.

Education should be encouraged and expanded. Everyone should have the opportunity to personally develop their own exceptional innate abilities and unlock their creativity.

But except for the personal development benefit to advancing one’s education, the reality is that far less “educated” people will be necessary in the long term to produce the products and services necessary and valued by society. This is due to the exponential development of human-level artificial intelligence, which is embodied in advanced automation and robotics.

Those college graduates who do succeed within the fields of science and engineering are hired workers to do what? Our scientists, engineers, and executive managers, who are not owners themselves of the companies they work for, except for those in the highest employed positions, are encouraged to work to destroy employment by making the capital owners’ assets more productive. How much employment can be destroyed by substituting machines for people is a measure of their success –– always focused on producing at the lowest cost.

We need to realize that full employment is not a function of businesses. Companies strive to keep labor input and other costs at a minimum. Private sector job creation in numbers that match the pool of people willing and able to work is constantly being eroded by physical productive capital’s ever-increasing role.

We need to reform and restructure our economy and set as the GOAL broadened private, individual ownership of future wealth-creating, income-generating productive capital assets among ALL Americans, with capital estates ever building as the economy grows. Without a policy shift to broaden productive capital ownership simultaneously with economic growth, further development of technology and globalization will undermine the American middle class and make it impossible for more than a minority of citizens to achieve middle-class status. By changing course, over time and within a few decades, our “machined-powered” growth economy would produce greater wealth, and widespread private, individual ownership would assure prosperity, opportunity, and general affluence for every citizen. Broadened productive capital ownership would strengthen our democracy and individuals and families would be less or non-dependent on government welfare, whether disguised or not.

This prosperous society is achievable because, fortunately, in the near term, we can begin to grow our way out of the swelling unemployment and underemployment by increasing our investment significantly as a ratio of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) resulting in double-digit growth, while simultaneously broadening private, individual ownership of future income-producing productive capital investments, thus initiating the process of empowering every man, woman, and child to build over time a viable capital estate and reap the income generated. The key operative is BROADEN OWNERSHIP. Such investment would, in the short term, generate millions of new “real” productive jobs. The result would not only be that the GDP would dramatically grow but tax revenues from the high rate of economic growth would enable us to balance the federal budget, fully fund Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, provide Universal Health Care, Universal University Education, lower tax rates, and maintain a strong military, all simultaneously.

We have the opportunity to free economic growth from the “enslavement” of human labor and from the financial mechanisms that are based on the slavery of past savings. Technological progress, though, is no longer dependent on the number and quality of human workers. This fact will become obvious eventually to anyone who can think and analyze as they realize the reality that human labor will cease to be the primary source of wealth production in the future. As a result we can expect over the long term that unemployment and underemployment will remain high indefinitely. But the difference will be that people will drop out of the labor force voluntarily because they will be able to live off their dividend earnings via their ownership portfolios. This will create swelling demand for human workers who want to continue working. And with both dividend and wage and salary incomes for everyone there will be more customers to purchase the products and services produced, which in turn will create further dividends and earnings, which will create more customers, etc.

While the future holds less promise for universal job employment due to the ever-progressing contribution of technological-driven production using human-intelligent machines, super-automation, robotics and digital computerized operations, the jobs that will be in demand will require some mastery of technology, math, and science. As long as working people are limited by earning income solely through their labor worker wages, they will be left behind by the continued gravitation of economic bounty toward the top 1 percent of the people that the system is rigged to benefit. If we don’t re-chart our economic policies to broaden private, individual ownership of new productive capital formation, then more troubling is that the continued stagnation of the American economy will further dim the economic hopes of America’s youth, no matter what their education level. The result will have profound long-term consequences for the nation’s economic health and further limit equal earning opportunity and spread income inequality. As the need for labor decreases and the power and leverage of productive capital increases, the gap between labor workers and productive capital asset owners will increase, and the conditions will become very frightening and very chaotic.

Sadly, our leaders are not prepared and are not preparing the American people for the coming economic collapse and the next Great Depression, due to their lack of wisdom and foresight to understand that full employment is not an objective of businesses and private sector job creation opportunities are constantly being eroded by physical productive capital’s ever increasing role––as the use of human-intelligent machines, super-automation, robotics, digital computerized operations, etc. replaces labor workers to produce products and services.

The question that requires an answer is now timely before us. It was first posed by binary economist Louis Kelso in the 1950s but has never been thoroughly discussed on the national stage. Nor has there been the proper education of our citizenry that addresses what economic justice is and what ownership is. Therefore, by ignoring such issues of economic justice and ownership, our leaders are ignoring the concentration of power through ownership of productive capital, with the result of denying the 99 percenters equal opportunity to become productive capital owners. The question, as posed by Kelso is: “how are all individuals to be adequately productive when a tiny minority (capital owners) produce a major share and the vast majority (labor workers), a minor share of total goods and service,” and thus, “how do we get from a world in which the most productive factor — physical capital — is owned by a handful of people, to a world where the same factor is owned by a majority — and ultimately 100 percent — of the consumers, while respecting all the constitutional rights of present capital owners?”

The path to prosperity, opportunity, and economic justice can be found in the writings about the Capital Homestead Act. For more overviews related to this topic see my article “The Absent Conversation: Who Should Own America?” published by The Huffington Post and by OpEd News.

Also see “The Path To Eradicating Poverty In America” and “The Path To Sustainable Economic Growth“, and the article entitled “The Solution To America’s Economic Decline.”

For an in-depth overview of solutions to economic inequality, see my article “Economic Democracy And Binary Economics: Solutions For A Troubled Nation and Economy” at http://www.foreconomicjustice.org/?p=11.