On November 21, 2017, Martin Wolf writes on Financial Times:

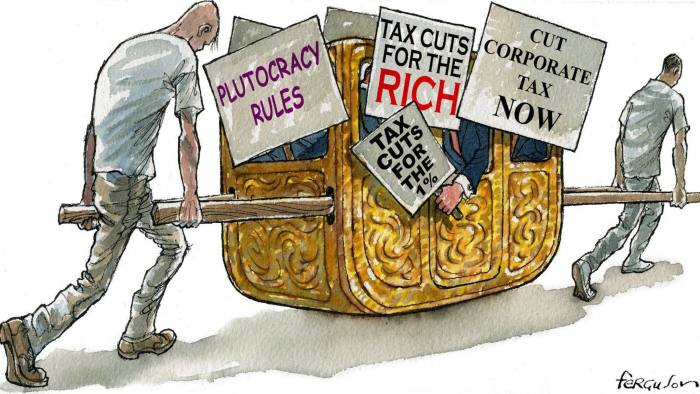

How does a political party dedicated to the material interests of the top 0.1 per cent of the income distribution win and hold power in a universal suffrage democracy? That is the challenge confronting the Republican party. The answer it has found is “pluto-populism”. This is a politically successful, but dangerous, strategy. It has brought Donald Trump to the presidency. His failure might bring someone more dangerous, more determined, to power. This matters to the US and, given its power, to the wider world.

The tax bills going through Congress demonstrate the party’s primary objectives. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in the House version of the bill, about 45 per cent of the tax reductions in 2027 would go to households with incomes above $500,000 (fewer than 1 per cent of filers) and 38 per cent to households with incomes over $1m (about 0.3 per cent of filers). In the more cautious Senate version, households with incomes below $75,000 would be worse off. This simply is reform for plutocrats. (See charts.)

That is far from all. The bill might also increase the cumulative fiscal deficit by about $1.5tn over the coming decade. Yet, according to the independent and respected Congressional Budget Office, the US fiscal position is already on a deteriorating path, with spending forecast to rise from 21 per cent of gross domestic product in 2017 to 25 per cent in 2028-37. The planned tax cuts would worsen the pressure to cut spending. The outcome desired by the Republicans is to slash spending on nearly all of the non-defence discretionary spending of the federal government, plus its spending on health and social security.

In all, then, this is a determined effort to shift resources from the bottom, middle and even upper middle of the US income distribution towards the very top, combined with big increases in economic insecurity for the great majority.

How, one must ask, has a party with such objectives successfully gained power? In all, we can see three mutually supportive answers to this question.

The first approach is to find intellectuals who argue that everybody will benefit from policies ostensibly benefiting so few. Supply-side economics, with its narrow focus on tax cuts, has been the main theory employed, because it directly justifies tax cuts for the very wealthy. But it is untrue that the tax cuts of the Reagan era unleashed an upsurge in trend US economic growth. Since the economy is now nearing full employment, the benefits of fiscal stimulus would be especially small.

Supporters of the proposed cuts argue that the reductions in corporation tax will lead to a big rise in business investment. Here are two powerful pieces of contrary evidence: the share of post-tax profits in US GDP has already nearly doubled since the early 2000s, with no beneficial effect on the rate of investment; and the UK has progressively slashed its corporate tax rate from 30 to 19 per cent since 2008 with no identifiable benefit for investment. Lowering the corporate tax rate is merely a windfall for shareholders. If one wanted to raise investment, one would make it fully deductible from tax. The proposed repeal of the estate tax, which is of benefit only to the heirs of the largest 0.2 per cent of estates in the country, really gives the supply-side game away. Who wants to argue that people live longer if death is less taxed?

The second approach is to abuse the law. One way has been to give wealth the overriding role in politics it holds today. Another is to suppress the votes of people likely to vote against plutocratic interests, or even disenfranchise them.

The third approach is to foment cultural and ethnic splits. This is sometimes described as the “Southern strategy”, which shifted the old South from the Democrats to the Republicans, after the former enacted civil rights. Yet this is too limited a view of the strategy. More interesting is the echo of the antebellum South itself. The pre-civil war South was extremely unequal, not just in the population as a whole, which included the slaves, but even among free whites. A standard measure of inequality jumped by 70 per cent among whites between 1774 and 1860. As the academics Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson note, “Any historian looking for the rise of a poor white underclass in the Old South will find it in this evidence.” The 1860 census also shows that the median wealth of the richest 1 per cent of Southerners was more than three times that of the richest 1 per cent of Northerners. Yet the South was also far less dynamic.

The South was a plutocracy. In the civil war, whose stated aim was defence of slavery, close to 300,000 Confederate soldiers died. A majority of these men had no slaves. Yet their racial and cultural fears justified the sacrifice. Ultimately, this mobilisation brought death or defeat upon them all. Nothing better reveals the political potency of tribalism.

A not dissimilar threat arises for today’s plutocrats. The economics and politics of pluto-populism have stoked cultural, ethnic and nationalist anger in the party’s base. Skilful demagogues are able to exploit this anger for their own purposes. At least Mr Trump remains a servant of the plutocracy. But his former adviser, Steve Bannon, seeks someone to promote rightwing populism shorn of its more blatantly plutocratic elements.

The plutocrats are riding on a hungry tiger. The pluto-populism of the Republican elite brought forth Mr Trump. This is not going to be forgotten. If the current tax bills get through, the tensions within the US are almost certain to get worse. Latin American inequality leads to Latin American politics. The US the world once knew is drowning in a tide of unconscionable and apparently unlimited greed. We are all now doomed to live with the unhappy consequences.

https://www.ft.com/content/e494f47e-ce1a-11e7-9dbb-291a884dd8c6