The fight to expand democratic control over the workplace just received a major shot in the arm.

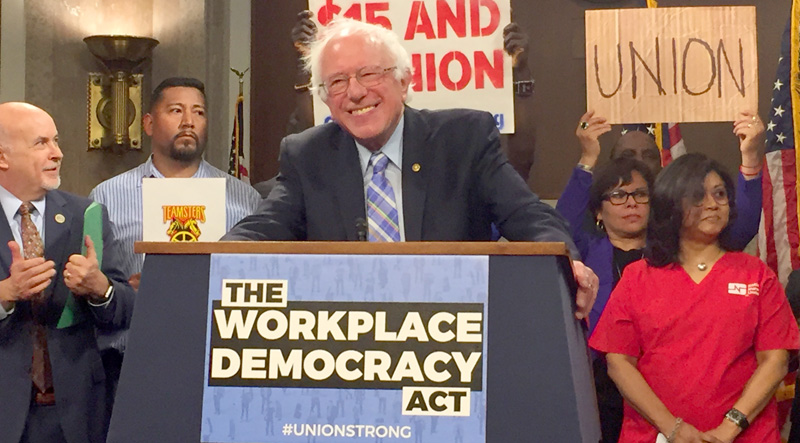

Today, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) introduced sweeping legislation that would dramatically expand labor rights, making it easier for workers to join unions, speed up contract negotiations, roll back “right to work” laws and clamp down on union-busting tactics by employers.

The legislation, known as the Workplace Democracy Act (WDA), is being co-sponsored by Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc.) and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) and has been endorsed by more than a dozen major unions and labor groups.

At an event on Wednesday announcing the legislation, Sanders said: “If we are serious about reducing income and wealth inequality and rebuilding the middle class, we have got to substantially increase the number of union jobs in this country.”

If passed, the legislation would redistribute power on the job to vastly benefit workers over their employers. And it would do so by extending democracy to the place Americans spend much of their waking lives.

In the United States, the concept of democracy generally conjures images of voting booths and candidate forums. But every time workers come together to advocate their interests and challenge concentrated power, they are practicing democracy. In daily life, one of the most important—and universal—arenas for this form of democratic action is the workplace.

Corporations and employers hold enormous power over workers, dictating which hours of the day they’re at work, what they’re allowed to say on the clock, what they wear and when they can go to the bathroom. Employers also determine workers’ wages as well as the type of healthcare they receive (if any)—all with the dangling threat of losing their job if at any time a boss decides they are expendable.

This slanted power dynamic is what allows employers to keep workers compliant even under abhorrent conditions. And it is why the role of labor unions—the primary vehicle for advancing democracy in the workplace—is absolutely critical to protecting workers’ rights at a time of unchecked corporate power.

Enshrining labor rights

The WDA would simplify the process of unionization by allowing the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to certify a union if a majority of eligible workers say they want to join. That process, commonly called “card check,” would eliminate union elections and give workers a clearer pathway to organizing their workplaces.

As it currently stands, employers have wide-ranging power to influence and intimidate workers into voting against unionization. They commonly force employees to attend anti-union meetings and threaten workers involved in organizing campaigns. The WDA would curb this type of behavior and create a more level playing field during union drives.

Labor advocates believe such reform is critical to giving workers a stronger voice on the job. In an interview with In These Times, David Johnson, National Field Director for the National Nurses United (NNU)—which has endorsed the legislation—says the WDA “is an important step forward in restoring what should be worker’s constitutional rights to engage in concerted activity to freely associate and to form strong unions to advocate for themselves and, in the case of registered nurses, to advocate for their patients as well.”

The legislation would also repeal section 14(b) of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which has allowed 28 states to pass laws restricting the ability of unions to collect dues from members who benefit from collective bargaining agreements. Such “right to work” laws have weakened unions in these states and led to lower overall pay for workers.

Under the WDA, employers would also be required to enter into contract negotiations within 10 days of a new union being formed. A full 37 percent of new unions go without a first contract for at least two years because of employers dragging their heels on negotiations. Such practices would be ended by this legislation.

As Sanders explained when introducing the bill: “Corporate America understands that when workers become organized, when workers are able to engage in collective bargaining, they end up with far better wages and benefits… and that is why, for decades now, there has been a concentrated well-organized attack on the ability of workers to organize.”

A more democratic economy

The push for the WDA—a version of which was originally introduced in 2015—comes on the heels of an announcement that Sanders’ office will soon propose a federal jobs guarantee. While the specifics have not yet been revealed, at its core such a program would seek to create a system of full employment in the United States, offering a job paying $15 an hour to any worker who wants one.

Once enacted, such a plan would have the potential to fundamentally shift the relationship of workers to their employers. If a job were always available through the government, workers would no longer live under the constant threat of losing their livelihood whenever their boss decides they are no longer needed. By setting a floor with a living wage, this form of a jobs guarantee would likely lift up the pay and benefits of workers everywhere, and open the space for more union activity in the private sector.

The combination of the WDA and a jobs guarantee, taken together with proposals for instituting Medicare for all, a federal $15 minimum wage and paid family leave, represents a barrage of progressive changes to the U.S. economy that would lift millions out of poverty and bring more democracy into workers’ daily lives.

Other senators have also recently voiced support for a version of a jobs guarantee, including Gillibrand and Cory Booker (D-N.J.). And the demand is not new in American politics: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously fought for full employment as a means to end poverty and advance the cause of racial justice.

Misery into progress

King was a staunch supporter of union rights throughout his life. In 1965, he gave a speech to the state convention of the Illinois AFL-CIO in which he called the labor movement “the principal force that transformed misery and despair into hope and progress.” King’s last major campaign before he was assassinated in April, 1968 involved joining with striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn. to win justice and dignity on the job.

In 2018, 50 years after King’s death, the U.S. labor movement is facing monumental threats. The Supreme Court will soon rule on Janus vs. AFSCME, a case that is poised to deal a severe blow to public-sector unions. President Trump is overseeing a massive rollback of workers’ rights and stacking the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) with appointees who are outwardly hostile to unions.

Corporate entities such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) have engaged in a decades-long campaign to weaken the power of labor, and today unionization rates in the United States stand at among their lowest levels in generations.

As NNU’s Johnson says, “I think we should be clear: There is a relative handful of incredibly wealthy, powerful mostly white men who are standing in the way of working people having the kind of country we deserve, where people have rights and they have decent wages and a decent community and a safe and healthy workplace, and education and healthcare as human rights.”

However, there are also signs of hope.

In states across the country, from West Virginia to Oklahoma, Arizona and Colorado, teachers have waged statewide strikes to win higher pay and better working conditions. Rank-and-file caucuses are helping to transform their unions into more militant organizations, willing to take dramatic action to defend members and stand up to attacks.

Workers in a diverse array of industries, from media to universities, logistics and tech, are launching new union drives. And over the past two years, workers under the age of 35 have led an unprecedented surge in union membership, and are much more likely to view unions positively. Overall, labor unions are now viewed more favorably by the public than they have been in well over a decade.

At a time of staggering economic inequality, when corporate profits are soaring while the safety net is shredded and working people are forced to scramble over crumbs, the renewed interest in labor unions is a sign that Americans are coming to see collective action as the best way to improve their living conditions and wrest workplace power from profit-obsessed employers.

While the WDA may be a dead letter under Trump and the GOP Congress, it does plant a flag for how a more democratic economy could be structured. And with a potential political sea change on the way in coming election cycles, this type of bold proposal sets the contours for what progressive politicians and activists alike can demand.

As workers are proving across the country, winning a better standard of living is possible, but it can only come about through demanding—and practicing—democracy on the job.

Gary Reber Comments:

Walter Reuther, President of the United Auto Workers was quoted as saying: “The breakdown in collective bargaining in recent years is due to the difficulty of labor and management trying to equate the relative equity of the worker and the stockholder and the consumer in advance of the facts…. If the workers get too much, then the argument is that that triggers inflationary pressures, and the counter argument is that if they don’t get their equity, then we have a recession because of inadequate purchasing power. We believe this approach (progress sharing) is a rational approach because you cooperate in creating the abundance that makes the progress possible, and then you share that progress after the fact, and not before the fact. Profit sharing would resolve the conflict between management apprehensions and worker expectations on the basis of solid economic facts as they materialize rather than on the basis of speculation as to what the future might hold…. If the workers had definite assurance of equitable shares in the profits of the corporations that employ them, they would see less need to seek an equitable balance between their gains and soaring profits through augmented increases in basic wage rates. This would be a desirable result from the standpoint of stabilization policy because profit sharing does not increase costs. Since profits are a residual, after all costs have been met, and since their size is not determinable until after customers have paid the prices charged for the firm’s products, profit sharing as such cannot be said to have any inflationary impact upon costs and prices…. Profit sharing in the form of stock distributions to workers would help to democratize the ownership of America’s vast corporate wealth.” [Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, February 20, 1967.]

Reuther also stated: “Profit sharing in the form of stock distributions to workers would help to democratize the ownership of America’s vast corporate wealth which is today appallingly undemocratic and unhealthy. The Federal Reserve Board recently published data from which it is possible to estimate the degree of concentration in the ownership of publicly traded stock held by individuals and families as of December 1962. Preliminary analysis of these data indicates that, despite all the talk of a “people’s capitalism” in the United States, little more than one percent of all consumer units owned approximately 70 percent of all such stock. Fewer than 8 percent of all consumer units owned approximately 97 percent—which means, conversely, that the total direct ownership interest of more than 92 percent of America’s consumer units in the corporation-operated productive wealth of this country was approximately 3 percent. Profit sharing in a form that would help to correct this shocking maldistribution would be highly desirable for that reason alone.… If workers had definite assurance of equitable shares in the profits of the corporations that employ them, they would see less need to seek an equitable balance between their gains and soaring profits through augmented increases in basic wage rates. This would be a desirable result from the standpoint of stabilization policy because profit sharing does not increase costs. Since profits are a residual, after all costs have been met, and since their size is not determinable until after customers have paid the prices charged for the firm’s products, profit sharing as such cannot be said to have any inflationary impact upon costs and prices.” [Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee of Congress on the President’s Economic Report, February 20, 1967.]

The labor union movement should transform to a producers’ ownership union movement and embrace and fight for economic democracy. They should play the part that they have always aspired to — that is, a better and easier life through participation in the nation’s economic growth and progress. As a result, labor unions will be able to broaden their functions, revitalize their constituency, and reverse their decline.

Unfortunately, at the present time the movement is built on one-factor economics — the labor worker. The insufficiency of labor worker earnings to purchase increasingly capital-produced products and services gave rise to labor laws and labor unions designed to coerce higher and higher prices for the same or reduced labor input. With government assistance, unions have gradually converted productive enterprises in the private and public sectors into welfare institutions. Binary economist Louis Kelso stated: “The myth of the ‘rising productivity’ of labor is used to conceal the increasing productiveness of capital and the decreasing productiveness of labor, and to disguise income redistribution by making it seem morally acceptable.”

Historically and in its present form, the labor movement is destructive in that it agrees with the idea that propertyless people should exist to serve those who own property. The labor movement doesn’t seek to end wage slavery; it merely seeks to improve the condition of the wage slave. If it actually cared about human rights and freedom, it wouldn’t call itself the “labor movement.”

Kelso argued that unions “must adopt a sound strategy that conforms to the economic facts of life. If under free-market conditions, 90 percent of the goods and services are produced by capital input, then 90 percent of the earnings of working people must flow to them as wages of their capital and the remainder as wages of their labor work… If there are in reality two ways for people to participate in production and earn income, then tomorrow’s producers’ union must take cognizance of both… The question is only whether the labor union will help lead this movement or, refusing to learn, to change, and to innovate, become irrelevant.”

Unions are the only group of people in the whole world who can demand a real, justice managed Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), who can demand the right to participate in the expansion of their employer by asserting their constitutional preferential rights to become capital owners, be productive, and succeed.

The ESOP can give employees access to capital credit so that they can purchase the employer’s stock, pay for it in pre-tax dollars out of the earnings generated by the new assets that underlie that stock, and ,and accumulate it in a tax haven until they retire,whereby they continue to be productive capital earners receiving income from their capital asset ownership stakes.This is a viable route to individual self-sufficiency needing significantly less or no government redistributive assistance.

The unions should reassess their role of bargaining for more and more income for the same work or less and less work, and embrace a cooperative approach to survival, whereby they redefine “more” income for their workers in terms of the combined wages of labor and capital on the part of the workforce. They should continue to represent the workers as labor workers in all the aspects that are represented today — wages, hours, and working conditions — and, in addition, represent workers as full voting stockowners as capital ownership is built into the workforce. What is needed is leadership to define “more” as two ways to earn income.

If we continue with the past’s unworkable trickle-down economic policies, governments will have to continue to use the coercive power of taxation to redistribute income that is made by people who earn it and give it to those who need it. This results in ever deepening massive debt on local, state, and national government levels, which leads to the citizenry becoming parasites instead of enabling people to become productive in the way that goods, products, and services are actually produced.

When labor unions transform to producers’ ownership unions, opportunity will be created for the unions to reach out to all shareholders (stock owners) who are not adequately represented on corporate boards, and eventually all labor workers will want to join an ownership union in order to be effectively represented as an aspiring capital owner. The overall strategy should assure that the labor compensation of the union’s members does not exceed the labor costs of the employer’s competitors, and that capital earnings of its members are built up to a level that optimizes their combined labor-capital worker earnings. A producers’ ownership union would work collaboratively with management to secure financing of advanced technologies and other new capital investments and broaden ownership. This will enable American companies to become more cost-competitive in global markets and to reduce the outsourcing of jobs to workers willing or forced to take lower wages.

Kelso stated, “Working conditions for the labor force have, of course, improved over the years. But the economic quality of life for the majority of Americans has trailed far behind the technical capabilities of the economy to produce creature comforts, and even further behind the desires of consumers to live economically better lives. The missing link is that most of those un-produced goods and services can be produced only through capital, and the people who need them have no opportunity to earn income from capital ownership.”

The union movement should also expand beyond representing corporate employees and represent capital ownership empowerment for all propertyless citizens.