on April 16, 2019, Richard Florida writes on Popular Resistance:

America’s Growing Geographic Divide Derives From Economic Inequality, Especially The Tremendous Gains Of The 1 Percent.

The two gravest challenges facing America today, economic inequality and geographic divides, are increasingly intertwined. Economic inequality has surged with nearly all the growth being captured by the 1 percent, and the economic fortunes of coastal superstar cities and the rest of the nation have dramatically diverged. These two trends are fundamental to a new study by Robert Manduca, a PhD candidate in Sociology and Social Policy at Harvard University. The study uses census microdata culled from 1980 to 2013, and finds that America’s growing regional divide is largely a product of national economic inequality, in particular the outsized economic gains that have been captured by the 1 percent.

Up until now, most researchers have believed America’s rising geographic divides to be a consequence of the way people sort themselves by education, occupation, and income. In Bill Bishop’s influential book, The Big Sort, the basic idea is that more skilled, affluent, and educated Americans move to the booming parts of the country—superstar cities like New York and Los Angeles and tech hubs like San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston—leaving the rest stuck in less-advantaged parts of the country.

To some, this is simply the effect of the clustering of talent and skill. For others, it is the result of the preferences of advantaged groups for amenities and other lifestyle factors. Some also say it is the consequence of land-use restrictions, which limit the development of economically successful places, or other barriers to growth. Manduca does not deny that these kinds of geographic sorting forces are in play. Instead, he finds that the staggering growth in the economic divide helps to magnify such spatial division. The rich and the poor occupy different places to begin with, so as income inequality rises, the geographic discrepancies also rise as a consequence, with rich places getting richer and poor places falling further behind. Or as he puts it: national inequality acts like a powerful wave that “washes over an uneven landscape, leaving behind deep pools in some areas and shallow puddles in others.” The rise in economic inequality, even though not inherently spatial, does in fact have spatial consequences.

This growing pattern of spatial inequality can be clearly seen in the maps below. In 1980, there were only two U.S. city-regions, Washington, D.C., and the New Jersey suburbs of New York City (in dark blue on the map), where mean family income was more than 20 percent higher than the national average. Most of the rest of the map is shaded in gray (indicating mean family income ranges between 10 percent higher or lower than the national average) or light red, with some pockets of dark red.

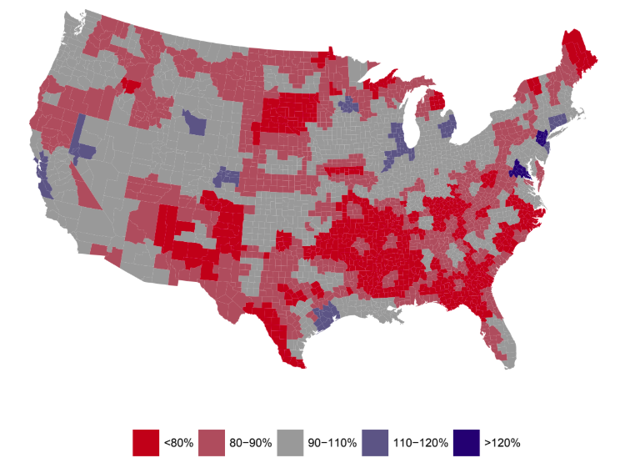

Commuting zone mean family income relative to the nation, 2013

The map for 2013 is very different. Now we see many more regions shaded in dark red than before, indicating the mean family income is less than 80 percent of the national level. At the same time, there are many more—and larger—bands of dark blue. The blue of the Washington, D.C., region grew to include more of Virginia and Maryland, and the blue New York City region grew to include more of New Jersey and Connecticut. Plus, the Bay Area, Boston, and Minneapolis, are now blue on the map.

Changes in commuting zone mean family income relative to the nation, 1980–2013

The pattern can also be seen in the scatter graph above which compares mean family income for U.S. regions in 1980 to mean family income in 2013. Coastal metros like New York and its suburbs, Boston, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., are above the line. These places, which were already more affluent in 1980 have grown even more so by 2013. But other city-regions—a few large ones like Detroit, Phoenix, and Miami, and many more small ones—are below the line, indicating the relative decline in their economic fortunes.

In the more than three decades spanning 1980 to 2013, Manduca finds that the share of Americans living in affluent metro areas (those with incomes 20 percent higher than average) rose nearly four-fold, from 4 percent to 16 percent, while the share of Americans living in poor metros (those with incomes 20 percent lower than the national average) also rose from 12 percent to 31 percent. Putting both of these trends together, the share of Americans living in either rich and poor metro areas (those where incomes were either 20 percent higher or lower than the national average) nearly tripled from 1980 and 2013, rising from 12 percent to more than 30 percent. The “middle” is disappearing, as more Americans are in one of the extremes.

But what has produced such staggering growth in spatial inequality? Manduca employs a variety of statistical techniques and counterfactual simulations to parse whether spatial inequality is a product of geographic sorting, or a product of people getting richer and poorer while staying in place.

Indeed, fully half of growth in spatial inequality over the past three decades can be pinned on the economic gains of the 1 percent, with the rest of the top 10 percent of income earners accounting for an additional 25 percent of America’s geographic divide. As the 1 percent has hauled in a growing share of the economic pie, the places where they live have pulled away from the rest of the country. “Income sorting has played a role in driving regional divergence, but income inequality has played a larger one,” Manduca writes. Using a counterfactual approach to compare the impact of geographic sorting and national income inequality based on 1980 baselines (before national inequality exploded), Manduca finds that: “If income inequality had remained constant at 1980 levels, the observed income sorting would have resulted in just 23 percent as much divergence as actually occurred. In contrast, even if there had been no income sorting whatsoever, growth in income inequality would have produced 53 percent of the observed divergence on its own.”

This suggests that many of the policy strategies advocated to deal with spatial inequality—such as place-based policies to build up lagging places, people-based policies to train them with more skills, or policies to increase housing supply—may help at the margin, but will ultimately not make much of a significant dent in America’s worsening regional divide. That’s because they fail to address a key underlying driver: national income inequality and its geographic consequences, where hugely outsized gains have gone to a very small fraction of America’s places. “Regional income divergence results in large part from national trends, which are generally attributed to changes in economic policy and the economic environment like financial deregulation … and declines in the real minimum wage, among others in the 1970s and 1980s,” Manduca told me via email. “This means that regional income disparities are a national problem.”

And this has implications for the way we think about and respond to different parts of the country. “We’re often too harsh on economically struggling regions,” he adds. “We tend to blame them for their troubles, and say that they’re not doing enough to attract or create high-paying jobs.”At the other end of the economic spectrum, we also tend to blame expensive cities and their onerous land use restrictions for their increasingly unaffordable housing. Instead, it’s more helpful to think about how these local trends are largely a consequence of national-level policy changes.

Coping with America’s escalating regional divide cannot, and will not, happen unless we grapple with the even larger national problem of structural inequality and its causes. “Narrowing the disparities between different parts of the country will be almost impossible without also reducing the total amount of income inequality between people,” Manduca adds. This narrowing will take a big change the rules to reduce the hold the 1 percent has on the economy and redistribute wealth to a much broader spectrum of society.

https://popularresistance.org/how-the-1-percent-is-pulling-americas-cities-and-regions-apart/

Gary Reber Comments:

This is an article reporting on the work of yet another academic who reports on the obvious, that economic inequality has surged with nearly all the growth being captured by the 1 percent, and with the poor getting poorer and the “middle” disappearing. Being rich means that one has more flexibility in choosing where one lives and that translates to “superstar” cities that offer geographic, cultural amenities, and brain trust headquartering compared to the rest of the nation. Rich places get richer and poor places get poorer in accordance with their wealth accumulations and the tax base to draw upon to support infrastructure development. Thus, we are witnessing the clustering of more Americans in one of the extremes.

The researcher presents no solutions that will address America’s worsening regional divide, stating that not even skills training for jobs will make a dent in this divide. All Robert Manduca can assess is that the underlying cause is “national income inequality” and that the solution is to “redistribute wealth to a much broader spectrum of society.”

I do not know why we are so inadequately educated and not realize that redistributing wealth, accumulated by those who are the most productive members of our society through their labor and their “tools”, will continue to stun our economy’s growth.

The author of the study obviously does not appreciate why the rich are getting richer and the poor, poorer. It should be obvious that the rich have a concentrated hold on the ownership and thus control of the “things” that are producing the bulk of the goods, products, and services needed and in-demand. In other words, we have shifted producing from broad labor intensive inputs to non-human capital instrument inputs narrowly owned by the 1 percent. We have been witnessing tectonic shifts in the technologies of production, which have and will continue to reduce the necessity for human labor, and thus devalue the worth of labor as more and more Americans compete for less and less jobs through which one can earn an affluent income. Workers who master skills to work with the evermore prevalent non-human capital factor of production will be able to be productive and earn a wage income, but they will be relatively few .

While the national focus is always on job creation instead of ownership creation, our scientists, engineers, and executive managers who are not owners themselves, except for those in the highest employed positions, are encouraged to work to destroy employment by making the capital “worker” owner more productive. How much employment can be destroyed by substituting machines for people is a measure of their success — always focused on producing at the lowest cost. Only the people who already own productive capital are the beneficiaries of their work, as they systematically concentrate more and more capital ownership in their stationary 1 percent ranks. Yet the 1 percent is not the people who do the overwhelming consuming. The result is the consumer populous is not able to get the money to buy the goods, products, and services produced as a result of substituting “machines” for people. And yet you can’t have mass production without mass human consumption made possible by “customers with money.”

We need to reform the monetary and financial system to free economic growth from artificial barriers that are restricting us from breaking free of anemic growth to create responsible, environmentally protective and enhanced growth to empower our building a future economy that can support general affluence for EVERY citizen, not limited by the 1 percent.

The solution is to empower EVERY citizen to be productive and earn to consume. So, if everybody who consumes, produces, and everybody who produces, consumes, things would work a lot better in the world. When people cannot produce, something must be done to meet their consumption needs, or what was a simple economic problem (how people can consume) turns into a major political problem (how to keep order in society when people are deprived and starving). Thus, what should be the major, if not sole focus of government — how to assist people in becoming and remaining productive is ignored. Instead, government implements policies seeking to guarantee that most if not all people have sufficient effective demand to enable them to consume when they do not or cannot produce. This in turn requires ever-increasing levels of government interference not only in the economy, but in every aspect of life.

Thus, logically, if productive capital is increasingly the source of economic growth, it should become the source of added property ownership incomes for all Americans. If both labor and non-human capital are independent factors of production, and if capital’s proportionate contributions are increasing relative to that of labor, then equality of opportunity and economic justice demands that the right to property (and access to the means of acquiring and possessing property) must in justice be extended to EVERY American citizen. Yet, sadly, the American people and its leaders still pretend to believe that labor is becoming more productive and couch all policy directions in the name of job creation. Americans ignore the necessity to broaden personal ownership of wealth-creating, income-producing capital assets simultaneously with the growth of the economy.

Significantly though, no matter how much labor is necessary or unnecessary, it is imperative that the issue of concentrated capital ownership is addressed, and policies are enacted to simultaneously create new capital owners of the corporations growing the economy as the economy grows.

How to accomplish this goal and create a plan should be our national focus. The solution entails monetary reform of the Federal Reserve and banking system, and the creation of financial mechanisms that do not require past savings to finance future growth. That means empowering EVERY child, woman, and man to acquire productive capital with the self-financing earnings of capital, and without the requirement of past savings (or past reductions in consumption).

Given financially feasible investments, i.e., investments that pay for themselves out of future profits and thereafter provide consumption income for the investor, there should never be a question of whether there’s enough savings accumulated in the economy to finance all the necessary new growth of building a future economy that can support general affluence for EVERY citizen. Using “future savings,” there can always be enough money in the economy — and past savings can effectively be spent on consumption, which is their purpose, as they represent unconsumed production from the past.

Thus, the most important economic right Americans need and should demand is the effective right to acquire capital with the earnings of capital. “Capital Homesteading” provides such a means.

Support the enactment of the proposed Capital Homestead Act (aka Economic Democracy Act and Economic Empowerment Act) at http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-a-plan-for-getting-ownership-income-and-power-to-every-citizen/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-summary/ and http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/ch-vehicles/. And The Capital Homestead Act brochure, pdf print version at http://www.cesj.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/C-CHAflyer_1018101.pdf and Capital Homestead Accounts (CHAs) at http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/ch-vehicles/capital-homestead-accounts-chas/.

Support Monetary Justice at http://capitalhomestead.org/page/monetary-justice.

Support the Agenda of The JUST Third WAY Movement (also known as “Economic Personalism”) at http://foreconomicjustice.org/?p=5797, http://www.cesj.org/resources/articles-index/the-just-third-way-basic-principles-of-economic-and-social-justice-by-norman-g-kurland/ and http://www.cesj.org/resources/articles-index/the-just-third-way-a-new-vision-for-providing-hope-justice-and-economic-empowerment/.

For an overview of this new paradigm, see “Economic Democracy And Binary Economics: Solutions For A Troubled Nation and Economy” at http://www.foreconomicjustice.org/?p=11