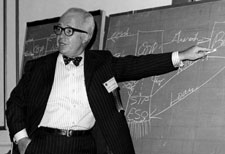

In March 1984, Louis O. Kelso delivered an address at the Air Line Pilots Association Retirement and Insurance Seminar in Washington D.C.:

In those days, I was constantly bothered by the oppressive effects of the depression. My father had lost his job, and my mother had a desperate time making ends meet with a little grocery store she had managed to put together to support the family.

I was impressed by the fact that our economy seemed to have the capability to climb out of the depression. By that, I mean it had then — as it has today — the raw materials, the technological know-how, the manpower, and the skills, along with enormous unsatisfied needs and wants. Those are the elements of a prosperous society producing and enjoying a high level of general affluence. But it wasn’t happening. And that really bothered me. Why wasn’t it happening? After all, here were grown-up people with all the means to make the economy go, and it wasn’t going.

We lived next to a railroad — the Colorado & Southern Railroad — that ran through Westminster. The passenger trains went by empty. They would have a couple of conductors, a brakeman, a fireman, and an engineer, but no passengers. The freight trains went by loaded — with people but no freight; millions of people were roaming the United States looking for jobs that didn’t exist. A large number of farms were untilled, except for the farmers’ own use; they couldn’t sell any surplus output.

I brooded about this situation and after a year or so struck upon a way to study it. The one thing everyone seemed to agree on was that this is a “capitalist” society, a capitalist economic system. Since the word “system” means “logic,” I thought to myself, I’ll just find out what that capitalist logic is. So I set to work reading as much as I could on history and economics while working my way through college and trying to keep up my grades.

After two or three years, I found the answer to my question: there wasn’t any logic; there wasn’t any theory of capitalism. “Capitalism” is a behavioral term. Up until World War I, when Britain was the great creditor nation of the world, anything that Britain did was considered capitalist. It didn’t make any difference what happened in the British economy. If it happened there, it was still capitalistic.

In World War II, the United States became the creditor nation, and after that capitalism was whatever the United States did in any official capacity or in any other context that supported our national interest.

Well, you don’t have to be too much of a genius to know that if you are talking about a system where nobody understands the logic, there must be something wrong. After all, it has all the earmarks of a system — that is, an arrangement for the production and distribution of goods and services, and the consumption of good and services — so it should follow some kind of natural law. Being undaunted at that early age, I was certain that I would figure it out.

By 1945, at the end of the war, I had written a manuscript for a book that, among other things, laid out a theory of capitalism. The manuscript was called “The Fallacy of Full Employment,” which referred to the fallacy of trying to solve the income distribution problem by relying on only one of the two ways that people participate in production to earn income.

In fact, the mixture of labor input and capital input had been rapidly changing for 200 years in step with the Industrial Revolution and had even been changing long before that with the discovery of the first tools. Alfred North Whitehead, I think, gave the best definition of the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. He said it was the point in history where “man invented the art of invention.” In other words, from about 1670 in Britain and 1776 in the United States, we no longer relied entirely on accidents, inspiration, or hunches to invent ways to improve the quality, quantity, and variety of goods and services and to save toil. Instead, the process became more and more specific. And with that, of course, industrial change accelerated at an exponential rate.

What I discovered was not a new economic theory, but a missing fact. Copernicus, after watching the stars and playing with the mathematical formulas that he thought explained their activities, concluded that geocentric theory was wrong. He deduced, instead, that all the heavenly bodies in our galaxy moved not around the earth, but around the sun.

But he was dealing with something that was so distant it couldn’t be easily seen or accurately measured. And when Galileo, almost a century later, picked up the same idea and tried to get it accepted by conventional science, the establishment almost fried him. They made him recant heliocentric theory to save his life. What each had discovered, without realizing it, was not a new theory, but a missing fact. You just couldn’t see it until the invention of the telescope.

Later, when Pasteur came forward with germ theory and struggled over much of his lifetime to get the medical profession to accept it, he was dealing not really with a new theory, but with a missing fact. The only problem was that the germs were so small you couldn’t see them until the invention of the microscope.

We don’t need telescopes and microscopes to understand the fact I want to talk about now. We do need shovels to dig through the tons of mythology that cover it up.

This is the missing fact: in the real world, goods and services are produced by two things, not just one. At present, the universally accepted idea is that, morally, if you want income, you must produce something; you must contribute to production something the public will buy. That’s the moral principle. Charity is a way to cope with the system when justice doesn’t work — that is, when someone can’t earn an income. Our national economic policy is: work is the only way. In other words, full employment. It doesn’t make any difference what’s going on in the scientific world or the business world or the industrial world, we still believe full employment will solve our income distribution problems. This is what major political figures have always maintained. Full employment is the national economic policy of Russia; it is the national economic policy of the United States, and it is the national policy of just about every nation on Earth.

I say we’ve left out a fact. A human individual can earn income just as legitimately through privately owned capital as through privately owned labor. By capital I mean land, structures, machines, and certain intangibles that have the characteristics of property, such as patents and trade names.

The whole function of technology is to change the way in which goods and services are produced from labor intensive to capital intensive. Let’s look at that for a moment. The American Constitution has a lot of undiscovered wisdom in it. In the field of economics, the constitutional wisdom couldn’t be discovered as long as men were locked into the mythology of one-factor economics.

The prologue to the Constitution — that is, the Declaration of Independence — recognizes in every person the right to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. What is the right to life? In economics, it is the right to earn income to support life. That’s not the way it’s being interpreted today. It’s being interpreted as the right to biological life, supported on other people’s earnings — “entitlements.” It means the “right” to be a dependent under the ever-more-dominant economic policy of coerced redistribution. Mere “trickle-down” isn’t the way it works; “coerced trickle-down” is.

The implications of this are profound. They call for very close scrutiny of our economic institutions. Because a society that falsifies how it earns its bread — that is, how it produces goods and services — and legitimates the right of individuals to buy food, shelter, and other things, is an immoral society from the top down and from the bottom up. If you want to know why immorality is beginning to pervade every area of our society, you can trace it to that. We lie about what’s going on in the world regarding our subsistence. We lie to live. That’s not a trivial matter.

In the two books which Mortimer Adler and I wrote, and in the third one I wrote with my wife, Patricia, the main message was simply this: as the production of goods and services changes from labor intensive to capital intensive, the way in which every person — not just a few, but every person — earns his or her income must change in the same way. You can’t do that unless two things happen: (1) you have to broaden the ownership of capital, and (2) you have to tighten up the laws of property so that the capital owners collect the wages of their capital with the same faithfulness that the labor workers now collect the wages of their labor.

At present, we do exactly the opposite. We pretend there is only one way to earn income — namely, to work. And we therefore conclude that it doesn’t really make any difference who owns the capital. Consequently, nobody gets very excited about the typical equity capital owner’s getting only one-twelfth of the income that flows from the assets represented by the stock he or she owns. Only one-twelfth! If you find that hard to believe, it’s easy to illustrate.

State and federal corporate income taxes, plus the employer’s share of Social Security — which does nothing for the employer — take over half of corporate net income. Over 50 percent goes to taxes. Boards of directors, lacking a logical way to finance growth, take up to three-fourths of what’s left. That leaves you with one-eighth or so of what you started with. And the infighting, under the advocacy system, between management and labor shrinks that eighth to a twelfth. About one-twelfth is what the shareholders get. Put another way, this means that capital, even in a badly structured economy, is about 12 times more powerful than it appears to be.

That takes me back to another historical note. The manuscript I finished as a young man came with me to San Diego on a destroyer in 1945. At that time, I looked around at what was going on in the United States. Congress was debating the Full Employment Act of 1945, which basically said there’s only one way to earn income. And I said to myself, “Louis, you’d better settle down and practice law, which is what you’re trained to do, and let the country recover from the war. Stick your manuscript in the closet, and if after 25 years you still think the thesis is valid, dig it out, update it, and publish it.” Well, I got about five years into the seasoning process, with no conversations about it, before Mortimer Adler, who had just finished his Great Books of the Western World, moved to San Francisco and set up his Institute for Philosophical Research.

Some of his patrons were clients of mine, and they introduced us, which led to my becoming his lawyer and helping him organize the Institute. About four years later, in the mid-1950s, he and I spent a weekend together at the ranch of Prentiss Cobb Hale, chairman of the board of Hale Brothers. We were sitting around the swimming pool after horseback riding, and Mortimer, who never forgets anything, said, “Lou, last winter, in one of the classes that you attended at the Institute, we were reading Marx and several other texts, and during the discussion you voted one way on a certain issue and everybody else, including me, voted the other way. What I’d like to know is how did you get on the other side of the argument?” At that point, I could see that the aging period of my secret manuscript was about to end. I said, “Mortimer, if I had taken any other position, it would have violated the theory of capitalism.” He said, “Oh, come on now; there isn’t any theory of capitalism. I’ve just finished putting together the Great Books of the Western World. I had more than a hundred scholars working under me. That was one of the questions we tried to answer. I can tell you there is no theory of capitalism.” I said, “Mortimer, I’m sorry, but your research is incomplete.” Well, naturally, he was a little irritated by that, so he said, “Give me the citation. Where do I find it?” I said, “In my closet.” He thought he’d been had. He said, “Wait a minute. Don’t come back here Monday morning bringing me a big pile of dog-eared papers. I don’t have time to read that kind of stuff. Just give me the five-minute version.” I said, “All right, the five-minute version is this: conventional wisdom has it that only labor produces wealth. Everybody knows that. But I discovered another fact. There are two ways to do it. You can do it through your privately owned labor power or through your privately owned capital.”

Mortimer jumped about 12 feet off the ground. “There’s no justice,” he said. “I’ve spent 22 years studying this subject, and you stumble across the answer with no effort at all.” Well, it may have looked like no effort to him, but I thought I had worked pretty hard at it.

Mortimer then started badgering me, saying, “You’re a coward for not speaking out on this. What do you care whether you get martyred; this is truth. The world needs it.” I said, “Yes, I understand, but I’m already working long hours, and I’ve just got to do it in my own time.”

He kept on bugging me, and finally, when he and I were in New York some months later, he came down to breakfast one morning and said, “Lou, I’ve got it! Suppose you and I take the highlights out of your manuscript and publish it under the title The Capitalist Manifesto?” So that’s what we did. We rewrote the manuscript four times in one month and sent it off to four publishers, all of whom accepted it. It made the best-seller list.

In that book, Adler took the view that what we were saying required some kind of reaction. Either you tried to refute it or you made some effort to apply it. Unfortunately, we got neither. It’s only now — 25 years later — that we’re starting to see some response.

In 1955, three years before publication of The Capitalist Manifesto, I was a junior partner in the third largest law firm in San Francisco. A client from the San Francisco peninsula had come in to talk with one of the partners about a legal transaction. The client had founded a local newspaper company. Now that he was almost 80 years old, he wanted to sell the newspaper to his employees. He was a good person. He said to his employees, “Believe me, if I were rich, I would give it to you. You’ve done a tremendous job building this paper. I want you to own it. But the paper is my entire capital estate. I have children and grandchildren to think about. I feel I have to leave as much of the estate to them as I can. So, do you want to buy it?” With one voice, they said, “Yes, we do.”

It happened that the No. 2 man at the newspaper — a fellow named Gene Bishop — had been my commanding officer in the Navy. It was he who sat down with the corporate finance people at our law firm. And the attorneys on the case called in Crocker Bank to make a survey of the employees to determine what kind of payroll deductions they could manage, how much savings they could invest, whether their houses would stand second mortgages, whether their relatives would put up money, etc.

A few weeks later, the bank called in the unions and announced its findings: “Gentlemen, we’ve got some good news and we’ve got some bad news. The good news is that you can afford to pay the interest on this purchase indefinitely. The bad news is that you can’t afford to pay the principal.” Well, the owner of the paper had in mind some generous terms, but not quite that generous.

When Gene Bishop passed my office that day, I said to him, “Hey, Gene, are you a newspaper owner now?” He said no and told me the story. I said, “Gene, I think it’s very possible you were given bad advice.” He looked around, a little shocked, and closed the door. “Do you know where you are?” he asked. I said, “Yes, I do, but you and I are old friends. I’m not going to lie to you. I don’t know for certain, but I think you were given bad advice.” He said, “What should we have done?” I said, “I don’t know yet. I would have to look at all the information. If you want me to, I’ll pull the file and tell you whether I think the deal can be done.” He said, “Listen, this is a life-and-death matter for me. I’m not going to stay with this newspaper if it’s going to be sold to Hearst or some other chain. I like it the way it is.”

The next day, after studying the file, I called him. “Gene,” I said, “this thing will fly like a birdie. You don’t have to take anything out of your pockets or out of your paychecks. You don’t have to mortgage your house. You don’t have to do any of those things. Five or six years downstream, the employees will own the business free and clear. And the present owner will have his money and his interest.” Gene thought I was kidding, but I was not.

Five months later, it was done; the deal was completed. And six years later, it was paid for. And the employees went on to work hard and make money. Even with seven unions, no adversary labor problems arose. They were all owners. Let me tell you what the logic of an ESOP is. I’ve spent my entire working lifetime in corporate finance — every major type: stocks, bonds, public issues, private issues, etc. The logic of capital acquisition — i.e., capital in the physical sense of the word (land, structures, and machines) — is self-liquidation.

Nobody who knows what he’s doing buys a capital asset or an interest in one unless he first assures himself, on the basis of the best advice he can get, that the asset will pay for itself within a reasonable period of time. The rule of thumb is three to five years — in a depression, maybe a little bit longer. And after it pays for itself, it is expected to go on producing income indefinitely with proper maintenance, with restoration in the economic sense through depreciation accounting, and with restoration in the technical sense through research and development. If it doesn’t produce indefinitely, you’ve made a mistake in one of those three areas.

In my early thinking on this, I kept coming back again and again to the question: if the logic of capital acquisition is to buy something that pays for itself, why do you have to be rich to buy it? Part of the answer is this: while most capital does pay for itself — and in a well structured economy it would pay for itself much more easily than it does in a badly structured economy that strangles the power of consumers to earn — still, there is at least a theoretical chance, and sometimes a very real chance, that it might not pay for itself, or it might not pay for itself in the projected time period. So, you’ve got a business risk.

The experts on business risk are the insurance underwriters. And they are the first to tell you that if it weren’t for commercial risk insurance, we wouldn’t have gotten far out of the Stone Age. That is to say, what is a disaster to one individual is something that can be quite easily absorbed over a broad base by collecting premiums in a pool that will provide emergency funds for those who actually suffer a loss. Now, the risk relating to capital — the feasibility risk — is no minor business risk. It is the most important of all business risks, because it determines whether men and women whose earning power is constantly eroded and wiped out by technological change can restore that earning power by owning capital. I’m not talking about handouts; I’m not talking about giveaways; I’m not talking about coercing someone to pay you more for doing less. I’m saying that what you have is a right to earn.

Thus, the feasibility risk is a very special kind of business risk. And how have we insured that risk? We’ve insured it with the worst possible kind of policy — a social disaster of cosmic magnitude. I’m talking about self-insurance. Self-insurance throws on the user of the capital instrument, or the entrepreneur, the feasibility risk.

When you take a financing plan to a banker and say, “Would you finance this?” he’ll examine every detail of the plan — your accounting work, your engineering work, etc. And if you finally convince him, he will say, “OK, I’ll make the loan.” Let’s say this business calls for a $1 million investment. Is he saying he’ll loan you $1 million? No, he’s not. He’s saying he’ll loan you one-half that amount, or maybe $600,000, or maybe $750,000. But the difference between the $1 million and the loan is a liability you take on. You’re the one who insures the feasibility risk. That’s what’s going on there.

Now, look what this means in the economy as a whole. It means we limit access to capital acquisition to those who already own capital — the rich. That’s why, when Benjamin Franklin estimated that colonial society had the ownership of its capital entirely in the top five percent of wealth holders — and it was an agrarian economy, so we’re talking primarily about land — he came up with an answer that every study, governmental and non-governmental, in the last 50 years has confirmed as true in our own time as well. All the productive capital in the American economy is today, as it was in the infancy of our nation, in the top five percent of wealth holders. Most of it, in fact, is owned by the top two percent.

We do not comprehend the meaning of that hidden fact. The way in which people produce goods and services is changing, but we don’t think that fact is important. We think there’s nothing wrong with letting a few people who have surplus wealth own just about everything in our entire economy. And I mean surplus wealth. All this talk about belt-tightening by people like the Rockefellers or the Gettys or the Hunt brothers or the Forbes 400 or any of 400,000 more families like those is simply hogwash. The only reason they’re talking about belt-tightening is that their fat bellies can’t hold any more. What such families are investing and risking is what I call “morbid capital.” It is capital they simply cannot and will not use for consumption because it is excessive. Remember, capital isn’t money; it’s measured in money, but it is really producing power and earning power. Capital is as vital as labor itself. And capital is coming in style, which labor is not.

When a person has a capital estate that enables him to earn all he can consume, he can pick his own standard of living. If he chooses to make a public jackass out of himself by overspending, let him. Society, sooner or later, will take care of that. The point is that in a free society you ought to be free to earn all that you desire to consume. But as to one percent more than that — no! Why?

Believe it or not, the answer to that is found in the common law of property. In the case of producer goods, the law of property — which has been taught for hundreds of years — is made up of a bundle of rights: the right to possess; the right to mine; the right to lease; the right to give away; the right to destroy; etc. All of those are the rights of a property owner. But there are two limitations on the property owner that have always been recognized in the common law: (1) the property owner is not empowered by the law of property to use his property in a way that injures the person or property of someone else, and (2) rights of property do not include the rights to impair the public welfare.

Now here is where Adam Smith comes in, in a way that even Adam Smithdidn’t understand. Production and the earning of income are facets of a single transaction. That is, the market forces that measure the value of an individual’s productive input also measure his income. They are two sides of the same thing, one looked at from the producer’s side, and the other from the consumer’s side.

Supply, according to Adam Smith, creates it own demand. That’s true, until you understand that there’s a missing fact. And that missing fact screws up every view of the market economy that fails to take it into consideration. Does supply create its own demand if you have on the production side of the equation a Gordon Getty with $2.5 billion of productive assets working for him? Does his production at that level make him a consumer of the income he can earn with $2.5 billion of capital? You know blooming well it doesn’t.

Now, let’s consider another basic fact: about 90 percent of the goods and services in the American economy are produced by capital, not by labor. Rand Corporation made a study a few years ago that said it was 98 percent, and I think you would be hard put to dispute it. That capital is owned by five percent of the people. Since production and consumption go together — except in the wonderful world of military boondoggle, where you don’t have to have any consumers except Uncle Sam — how does the economy work if five percent of the people are producing 90 percent of the goods and services? And keep in mind, the unsatisfied needs and wants of society are not in that five percent; those people are not the ones who are hurting.

Well, there’s a very simple answer. To the degree that the economy does work, it does so through redistribution. How do we redistribute? Here’s how: 55 percent of all federal taxes are levied on people who earn to give through transfer payments to people who need. Marx would have been delighted. That’s what he urged from the beginning. Likewise, 60 percent of state taxes, on the average, are levied on people who earn to give through transfer payments to people who need.

I estimate that a third of the American labor force is employed on boondoggle. What is boondoggle? Boondoggle is jobs that are federally subsidized to legitimate, in this hypocritical way, more and more incomes disguised as honest work. People resent having to part with their income or property to support strangers. That is human nature. So boondoggle is an attempt to hide the redistribution process from both giver and taker.

This brings us to the point that will probably get me thrown out of this meeting. The labor union movement at the present time is built on one-factor economics. Yet it is the only group of people in the whole world who can demand an ESOP, who can demand the right to participate in the expansion of their employer, and get away with it.

Let me give you an example. Norton Simon, Inc. was bought by Esmark a while back for $1 billion. I urged Dave Mahoney, the chairman of Norton Simon, with whom I have long been acquainted, to let us match the Esmark bid to buy the company for the employees and officers. He didn’t do it, and for a rather human reason. Here’s the story:

As you know, ESOPs enable employees to buy their employers. But most managements are accustomed to thinking only of their own stock acquisitions, their own golden handcuffs, and their own retirement security. Only the most enlightened managements realize that they can almost invariably sell the company to themselves and the employees at the same price they can sell the company to a conglomerate or a raider. In other words, the stockholders get paid the same amount. And while executives may sometimes be able to keep their jobs after a non-ESOP leveraged buy out, other employees often are not in that position. Furthermore, the ESOP leveraged buy out can solve the retirement security problems for virtually all employees, not just the few who negotiate the deal.

This is the time when a union representing some of the employees can assert what I believe is the constitutional preferential right of employees, when a company is being sold, to buy it for themselves through ESOP financing, so long as they can pay the same price any other buyer would pay.

If the American economy is not working properly because the earning power is in too few hands, every leveraged buy out except an ESOP buy out aggravates that problem many times over. Usually, in a single non-ESOP leveraged buy out, where public stockholders are selling, the number of stockholders is reduced from thousands to one or a handful of buyers. Had the ESOP leveraged buy out been used, the number of new stockholders would be equal to the number of employees. In the case of Norton Simon, Inc., executives of the company wanted to make one last big killing when they sold. I won’t give you the exact numbers, but they are impressive — even in a world dominated by corporate brigands. My company could have gained all the same advantages for management, while buying the whole billion dollar corporation for all the employees. We were perfectly willing to do it, for reasons I will explain in a moment. But, knowing my interest in making the whole economy work and enabling people to become economically autonomous again, top management was afraid, I guess, that we might not be as protective of their advantages. So they sold to Esmark.

Why would we have been willing to structure an ESOP and arrange the financing for a $1 billion employee buy out and still make a cold killing for management? I’ll tell you why. To get a few million extra for decision-makers, while building a billion dollars’ worth of capital ownership into 40,000 families, is not too big a price to pay if that is the only way it can be done.

When you leaders in the American labor movement begin to wake up and understand what you can do — what your legal rights are, what your economic rights are, what your rights as citizens under the Constitution are —- then you can exploit the leveraged buy out on behalf of employees and assert their constitutional preferential rights to become owners.

Abraham Lincoln said the purpose of government is to do for the people what they cannot do for themselves. I believe that man is so structured that he cannot control his own greed. If he had been able to do that, we probably would never have emerged from the protozoic slime. I mean, it’s just the nature of the beast to think of himself first — if not exclusively. But nature had an economic plan for world society. Nature thought that economic autonomy — i.e., making every human capable of participating in production and earning the income he needs for himself and his dependents — was a good idea. It is an idea that agrees with the inner man. But the arrangement of “one person, one labor power” is about as far as nature can go. After that, it is up to government, labor, and management to devise the institutions that enable us, in the advanced industrial age that we live in, to earn our income by engaging in production in ways that are consistent with economic reality.

In America, we tried to solve the structural defect in human nature through redistribution. To a large degree, this meant taxation, but it also meant empowering labor unions to use coercion to rig the price of labor. Anybody who talks about a free market in the United States and doesn’t make an exception for the price of labor, which enters into almost every transaction, does not understand the system. We do not have a free market that determines the value of wages and salaries. We have a rigged market.

You want to know what deregulation did? The purpose of regulation is to hold the consumer still so that management and labor can gouge him. And that’s what has been going on for roughly a half century. Deregulation let the consumer escape. He may have been happy as a worker, but he was unhappy as a consumer because most of the consumption is done by the 95 percent of the population who don’t own any capital. You know that. And when the consumer escaped and could get things for a reasonable price, he bought from the lowest-price producers.

Now, there’s no use badgering the past; there’s no use trying to say, “Who did that, or who are we going to hang?” All we can do now is to figure out how we can get from here to there. How do we get from a world in which the most productive factor — capital — is owned by a handful of people, to a world where the same factor is owned by a majority — and ultimately 100 percent — of the consumers, while respecting all the constitutional rights of present capital owners?

Let’s get back to labor. When unions demand more and more pay for less and less work, it’s inevitable that certain things will happen. For example, when Mortimer Adler and I wrote our second book (in 1961), we predicted that if the United States continued to encourage technological advancement and continued trying to distribute the resulting increase in income through labor, three things would happen: (1) we would ravage our currency with inflation, (2) we would destroy the integrity of private property in capital, and (3) we would lose our markets to any lower cost foreign competitor who could get in. That was 1961. I don’t think I need to tell you what has happened since then.

What was true then is still true today. We should restore our economy to a democratic scale through ESOP financing rather than continue putting capital ownership in fewer and fewer hands. Donald Trump in New York owns 10,000 apartments. How many of those do you think he can live in? Not many. The few can’t produce for the many without making slaves of the many. The leveraged buy out that isn’t an ESOP buy out promotes a modern form of slave trade. This has to be stopped. Don’t worry about communism and socialism. The big cry out of Washington is that the socialists are coming. The heck they are. There’s no real movement in this country for public ownership of industry. Even in countries where they already have it — other than Russia, where you can’t dissent — they are trying to find a way out. But they are trying to escape it in ways that won’t work.

Let me tell you what the danger is. There are two forms of social power in the world (excluding force and fraud, which are both antisocial). The first is political power —- the power to make, interpret, administer, and enforce the laws. Political democracy is participation in that kind of power in ways that are satisfying to most people. The second form of social power is economic power — the power to produce goods and services. That’s pretty straightforward.

But when people talk about democracy in American history, they don’t realize that what they are really talking about is merely political democracy. They are almost completely ignorant of what went on and how it fits into the real world of today. In 1776, we began the political revolution that introduced political democracy into an economy that was already an economic democracy. Ninety-five percent of the productive input in colonial society came from labor. Dear old nature had it all worked out — one person, one labor power. Everyone could support himself. Everyone could buy a house and pay for it. Everyone could raise a family and expect to live reasonably well. That doesn’t mean people were affluent; they weren’t. We’re talking about pre-industrial society. Affluence comes from capital.

You can’t expect people to be affluent before you have technology and industry. By the standards of living in early America, the dominant form of capital — land — was cheap and plentiful. And you couldn’t do anything with it without labor, which was well paid in comparison with labor in Europe, where most of our ancestors came from. Thus, we had true democracy because we matched political democracy with economic democracy.

Where are we today? We have political democracy. But what about economic democracy? It has been going downhill since 1776. The reason is that the 1770s, by coincidence, were also the beginning of the Industrial Revolution (James Watt patented the steam engine in England in 1769). And the decline will continue if we don’t stop it. Today, we are a plutocracy in which 90 percent of the goods and services of society are produced by the five percent of the people who own all the capital. Plutocracy is the economic base for another form of government: fascism — the ownership of productive capital by the rich and by their institutions.

To reverse that process, we’ve got to use ESOP financing for business corporations, as well as other methods of finance which use ESOP logic. And the logical place to start is with organized labor. You have the right to be productive; the right to earn income. I believe you can make the case that you have a constitutional right to be productive — the right to acquire and own capital. On the basis of that case, the pilots of Eastern Air Lines could walk into management and demand, in collective bargaining, the use of an ESOP — not just to trade a single block of stock for wage concessions, but to redesign the future of the company and its employees. You want the assurance that as your employer grows, it builds ownership into its employees. All of them! It’s an unused power, an awesome but unused power.

But for something like this to happen, companies and their unions have to wake up to the possibilities. The wonderful thing about having stockholders as employees is that you have the best informed body of stockholders you can get. And with that, you eliminate inflation. When you are in a position to earn the wages of your capital as well as the wages of your labor, your company is in a position to be more competitive through lower labor costs, while achieving higher employee incomes through the employees’ capital.

What about employment in the brave new world I’m proposing? Lifetime employment, as I see it, is to enter the economic world as a labor worker, to become increasingly a capital worker as you go along, and at some point to retire as a labor worker and continue to participate in production and to earn income as a capital worker until the day you die. You won’t need Social Security; you won’t need redistribution; you won’t even need pensions and profit sharing, which are secret runners for the stock markets. Pensions make great incomes for the gambling trade and Wall Street firms, playing with guess who’s money? That’s right, yours! Eighty-five percent of the money churning through the stock market is pension money. The ESOP circumvents that. In a single transaction, you finance tools for the employer and ownership for the employees. The pre-tax yield of corporate assets of prosperous companies varies from 25 to 60 percent. The yield on secondhand securities is around five or six percent. Sure, with capital gains, you can get a little more, but don’t forget, that’s a zero-sum game; for every gainer, there’s a loser. Wall Street doesn’t fly any airplanes or raise any corn or do anything else in the way of producing goods and services. It just plays games with your dough. And when you take it out in pensions, you’re going to get less than the company put in for you. You have to; that’s the dynamics of it.

So let me leave you with one simple thought: start using the power you’ve got to acquire capital ownership in your employers and to make capital work for you. Your salary is only one-half of the equation. With the airline industry in a transition state, now is the time to put ESOPs in place so that you share in future earnings as full participants in a democratized capitalist economy. You shouldn’t settle for anything less.