On April 2, 2016, Victor Hwang writes on Evonomics:

Management thinking is in a rut. This is a harsh thing to say, but it must be said. Despite all the great brainpower being applied, the field of management is failing to provide the empirical, grounded, actionable guidance that organizations require in today’s economy.

How is that so? It’s because traditional tools of management lack an “ecological systems” point of view for thinking about organizational development. Leaders today have to understand how ideas grow in the context of their environments if they want to create economic value successfully and sustainably.

Most of what passes for novel thinking in management now is merely the slapping of new labels onto old ideas. Or worse, faddish exhortations. Yes, there continue to be huge numbers of business books and articles published every year. Some of them are interesting. Some of them add incremental value. Most of them, however, are neither interesting nor add great value. And none of them has truly shaped the industry profoundly, the way that Michael Porter or W. Edwards Deming accomplished decades ago.

So why is this? Have all great management concepts already been discovered? Has business strategy become commoditized forever?

The rut is not the fault of management thinking itself. It’s deeper than that. In fact, the failure of management thinking cuts to the heart of what we humans understand—or fail to understand—of our own economic lives. Through my work with numerous organizations—small and large, private and public, for-profit and non-profit—I’ve arrived at some perhaps surprising conclusions.

What we have not fully captured—as a human species—is the systemic process by which we turn ideas into useful things. On one hand, the traditional techniques of business administration have provided managers with tools for analytical strategy and rigorously quantified decision-making. On the other, businesses today are creating so much real-world value by turning decentralized ideas into innovative products and services, based on fuzzy notions like culture and creativity. You can think of it as a clash between two opposing worldviews. The battle might be described as rigor versus intuition. Hard versus soft. Or even numbers versus people.

This is not a new phenomenon. Walter Kiechel, author of Lords of Strategy: The Secret Intellectual History of the New Corporate World, puts it in historical context:

There are observers who maintain that much of what goes on in business organizations comes down to a struggle between those who see the enterprise largely through the lens of the numbers—sales figures, costs, budgets—and those who focus instead primarily on people, their energies, ambitions, and limitations. A gross oversimplification, of course, but one that approximates the argument between the two schools of strategy…. What we would be looking for in an alternative to the strategy model—a unified theory of management, if you will—would be a construct addressing each of the issues a company faces in dealing with people: how they were to be selected, trained, disciplined, compensated, motivated, managed, and led…

We can readily understand numbers, but we struggle mightily to understand people. In other words, the soft stuff is hard .

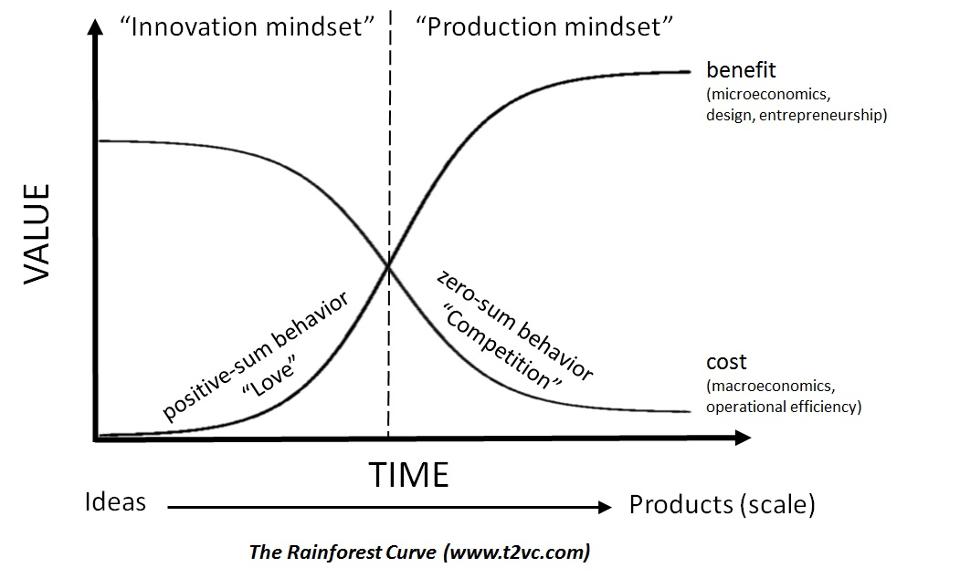

Here’s a simple diagram I’ve created, inspired by my collaboration with Stanford scholar Ade Mabogunje. It attempts to incorporate the two clashing worldviews and explain how they interrelate. It’s a proposed unified theory of management to show why so many good ideas fail to grow, why old businesses often die, and why certain businesses can thrive.

I call this diagram the Rainforest Curve. As ideas grow into products, from left to right, their beneficial value to someone increases. That’s the upward curve extending from the bottom left to the top right. The process of value creation is driven by positive-sum behaviors, like collaboration, team-building, and shared risk-taking. Think of the passion that a startup team invests in building their company.

You see this behavior manifested in real life by entrepreneurs, designers, inventors, artists, researchers, and innovators. As ideas grow, however, they cross a downward-sloping cost curve, which exerts real-world constraints. Those constraints include capital limitations, finite labor, or scarce resources. The cost curve is driven by zero-sum behaviors, like competition and squeezing out inefficiencies. Reducing the cost curve is what originally gave birth to the field of business strategy, as Kiechel chronicles.

The intersection, where the curves meet, is like an invisible brick wall. Most new ideas, great breakthroughs, and startup companies die on the left. Most aging institutions, corporations, and governments die on the right. The crossover is the hardest part.

Why is the crossover so difficult? The reason is that, as I’ve written previously, culture in business is primarily the clash between two opposing social contracts . One social contract is based on values of production, with its zero-sum norms. The other is based on values of innovation, with its positive-sum norms. Both social contracts are legitimate in their own ways, but they are completely opposite in effect. If we write the social contracts down, making the implicit explicit, here is what they look like:

| Rules of the Rainforest (positive-sum norms for innovation) 1. Break rules and dream 2. Open doors and listen 3. Trust and be trusted 4. Seek fairness, not advantage 5. Experiment & iterate together 6. Err, fail, and persist 7. Pay it forward |

Rules of the Plantation (zero-sum norms for production) 1. Excel at your job 2. Be loyal to your team 3. Work with those you can depend on 4. Seek a competitive edge 5. Do the job right the first time 6. Strive for perfection 7. Return favors |

Each of the two columns above is a sound worldview. They are valid in their own right. However, upon reflection, you realize that the two columns are perfectly opposed, item by item. And they lead to opposite results. The rules on the right side lead to productivity, efficiency, and predictability. The rules on the left side lead to creativity, serendipity, and uncertainty. Neither set of rules is wrong. The opposite of “trust” is not simply “distrust.” The opposite of “excel” is not simply “do a bad job.” People tend to see their own value choices as positive, not negative.

We can simplify these opposing social contracts even more, reducing them to the essential values being expressed. Each value below correlates to the corresponding rule above.

| Values of Innovation 1. Openness 2. Diversity 3. Serendipity 4. Fairness 5. Experimentation 6. Play 7. Giving |

Values of Production 1. Excellence 2. Loyalty 3. Dependability 4. Success 5. Quality 6. Precision 7. Reciprocity |

Successful companies must exist in both worlds—innovation and production—simultaneously. That’s hard to do. Innovators on the left often think of managers on the right as cold-hearted and lacking in vision. Managers on the right often think of innovators on the left as frivolous and impractical. But in reality, both sides need each other. Ideas that live only on the left side are stillborn. Institutions that get stuck on the right side become dinosaurs.

Good ideas fail because they cannot cross the cultural barrier between innovation and production. Silicon Valley’s success, arguably, comes from embracing the duality of both mindsets. For example, venture capitalists in the Valley must deal with hard numbers, but they’re also open to the idea that the next billionaire is a college dropout wearing a hoodie. You never know the next Zuckerberg, so keep your mind open. Put it another way: how well do your suits and hoodies get along? That’s dualistic thinking.

So what’s the future of management thinking? Despite recent history, I have faith that a revolution in management thinking is coming soon. Looking at the broader trend lines, we are starting to see the innovation cycle as a whole system, to understand the normative behaviors that undergird this cycle, and to construct practical tools to measure and accelerate the curve as ideas grow into reality.

In other words, a paradigm shift is fast approaching. It’s no longer enough to focus only on what’s easy to quantify—the traditional industrial approach. Managers and investors who know how to lead businesses as evolutionary processes—embedded in ecosystems—are most likely to succeed in the new paradigm.

That’s good news. Stay tuned, folks.

Gary Reber Comments:

This is what the Center for Economic and Social Justice (www.cesj.org) has to say about Justice Management:

What is Justice-Based Management(SM)?

Justice-Based ManagementSM (JBMSM) is a leadership philosophy and management system that applies universal principles of economic and social justice within business organizations. The ultimate purpose of JBMSM is to create and sustain ownership cultures that enhance the dignity and development of every member of the company, and to economically empower each person as an owner and worker.

JBMSM promotes a company’s long-term profitability within the global marketplace by enabling all worker-owners to serve and provide higher value to the customer. JBMSM connects every worker’s self-interest to the bottom-line and long-term success of the company.

The JBMSM process builds upon a written articulation of the philosophy and principles of the company’s leader (typically the CEO or chairman of the board) and leadership core group, in terms of universal principles and core values of the company. JBMSM proceeds in stages to build a consensus upon these fundamental shared values and vision of the company within each work area of the company.

These articulated values provide the foundation for enhancing the productiveness of workers and company profitability, and include such structures as employee-monitored economic incentive programs, participation and governance structures, two-way communications and accountability systems, conflict management systems and future planning and renewal programs.

The ESOP and Justice-Based ManagementSM

One of the main components of JBMSM is the “empowerment ESOP .” While the employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) was originally invented as a means for providing working people with access to capital credit to become owners of corporate equity, most ESOPs are set up as just another employee benefit plan or tax gimmick, or as an employee share accumulation plan (“ESAP”). Most ESOPs today are not designed to treat worker-owners as first-class shareholders. The “empowerment ESOP,” on the other hand, is designed to encourage workers to assume the responsibilities and risks, as well as the full rights, rewards and powers, of co-ownership.

Furthermore, all academic and government studies to date have concluded that ESOPs alone are not enough to affect individual and corporate performance. Within a JBMSM system, in combination with a regular gainsharing program tied to bottom-line profits, and structured systems of participatory management, the empowerment ESOP stimulates everyone in the company to think and act like entrepreneurs and owners.

Balancing Moral Values and Material Value

Justice-Based ManagementSM offers an ethical framework for succeeding in business. JBM balances moral values (treating people with fairness and dignity) with material value (increasing a company’s productiveness and profits while enriching all members of a productive enterprise). JBM’s three basic operating principles are:

Build the organization on shared ethical values—starting with respect for the dignity and worth of each person (employee, customer and supplier)—that promote the development and empowerment of every member of the group.

Succeed in the marketplace by delivering maximum value (higher quality at lower prices) to the customer.

Reward people commensurate with the value they contribute to the company—as individuals and as a team.

Justice-Based ManagementSM is guided by the concept of social justice, as articulated by the late social philosopher William Ferree, S.M. Social justice involves the structuring of social organizations or institutions (including business corporations) to promote and develop the full potential of every member.

JBM also embeds within an ownership culture the three principles of economic justice defined by the late lawyer-economist Louis Kelso and philosopher Mortimer Adler: (1) “participative justice,” or the right to the means and opportunity to participate in the economic process as an owner as well as a worker; (2) “distributive justice,” or the right to the full, market-determined stream of income from one’s labor and capital contributions; and (3) “social justice,” or the right and responsibility of each person to work in an organized way with others to correct the “social order” or institution when the principles of participative or distributive justice are being violated or blocked.

Within JBMSM the principles of social and economic justice provide a logical framework for defining “fairness” and structuring the diffusion of power within the corporation.

Structuring Ownership Participation

JBM is designed to systematize and institutionalize shared rights, responsibilities, risks and rewards within all company operational and governance structures involving:

Corporate values and vision

Leadership development and succession

Corporate governance and future planning

Operations (policies and procedures) and hardship sharing policies

Communications and information sharing

Training and education

Pay and rewards

Grievances and adjudication

A well-designed Justice-Based ManagementSM system sharpens and crystallizes the leader’s philosophy around “universal” principles, providing a solid foundation for a corporate culture that enables people to internalize these guiding principles. JBMSM generates organizational synergy by connecting each worker-owner to the financial tools of ownership (i.e., ESOP and profit sharing), participative management systems, and a defined share of power in the governance of the organization. This in turn enables people to make better decisions, discipline their own behavior, and work together more effectively and cooperatively—because it is truly in their self-interest to do so.

072303

ADDITIONAL SOURCES ON JUSTICE-BASED MANAGEMENT(SM)

For more information on Justice-Based Management(SM) and building an ownership culture, contact Equity Expansion International, Inc. at P.O. Box 40711, Washington, D.C. 20016, (Tel) 703-243-5155, (Fax) 703-243-5935, (Eml) info@eei-consultants.com, (Web) http://www.eei-consultants.com.

Also see:

“Justice-Based Management: A Framework for Equity and Efficiency in the Workplace” [pp. 189-210 in Curing World Poverty: The New Role of Property. [Originally titled, “Justice-Based Management: A Framework for Equity and Efficiency in the Workplace.”] Available for $15 plus $3.00 shipping and handling (in U.S.) from the Center for Economic and Social Justice, P.O. Box 40711, Washington, D.C., (Tel) 703-243-5155, (Fax) 703-243-5935, (Eml) thirdway@cesj.org, (Web) http://www.cesj.org.

“Beyond Privatization: An Egyptian Model for Democratizing Capital Credit for Workers” [pp. 247-258 in Curing World Poverty: The New Role of Property ] See above.

Journey to an Ownership Culture: Insights from the ESOP Community, ed. Dawn Kurland Brohawn, published by Scarecrow Press and The ESOP Association, 1997. Available from CESJ, $35.00 plus $3.00 shipping and handling (in U.S.).

“Theory O.” Available from National Center for Employee Ownership (NCEO), 1629 Telegraph Avenue, Suite 200, Oakland, California 94612, (Tel) 510-208-1300, (Fax) 510-272-9510, (Eml) nceo@nceo.org; (Web) http: //www.nceo.org).

Various publications of the Ohio Employee Ownership Center, 113 McGilvrey Hall, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242, (Tel) 330-672-3028, (Fax) 330-672-4063, (Eml) oeoc@kent.edu, (Web) http://www.oeockent.org/.

Various publications of the Foundation for Enterprise Development, (Web) http://www.fed.org.