On April 11, 2016, Jordan Brennan writes on Economics:

The emergence of economic inequality as a public policy issue grew out of the wreckage of the Great Recession. And while it was protest movements like Occupy Wall Street that brought visibility to America’s glaring income gap, academic economists have had a near monopoly on diagnosing why it is that inequality has worsened in the decades since 1980.

Monopolies rarely deliver outstanding service, and this is no exception. The economics profession is fond of believing that its theorizing is an impartial, value-neutral endeavor. In actuality, mainstream (‘neoclassical’) economics is loaded with suppositions that have as much to do with ideology as with science.

Take the distribution of income, which economists argue is (in the final analysis) a consequence of production. Whether one earns $10 per hour or $10 million per year, the presumption is that individuals receive as income that which they contribute to societal output (their ‘marginal product’). In this vision, the free market is not only the best way to efficiently divide the economic pie, it also ensures distributive justice.

But what if income inequality is shaped, in part, by broad power institutions—oligopolistic corporations and labor unions being two examples—such that some are able to claim a greater share of national income, not through superior productivity, but through market power?

In a study recently published with the Levy Economics Institute, I explore the power underpinnings of American income inequality over the past century. The key finding: corporate concentration exacerbates income inequality, while trade union power alleviates it.

Mass prosperity—the fabled ‘middle class’—was largely built between the 1940s and the 1970s. When President Roosevelt created the New Deal in 1935 union density was just eight percent. Density soared to nearly 30 percent by the mid-1950s, and the period spanning the 1930s to the 1970s would bear witness two major strike waves.

The combined effect was a surge in the national wage bill. In 1935 the share of national income going to the bottom 99 percent of the workforce was 44 percent. In tandem with strong unions and intense strike activity, the wage bill rose to 54 percent by the 1970s. In the period after 1980, union density and work stoppages both plummeted, pulling the wage bill down with them. American unionization is now just 11 percent and the wage bill sits at 41 percent—a seven decade-low for both metrics.

The declining power of the labor movement has many causes, but a series of state policies in the early 1980s hastened the demise. President Regan’s penchant for union busting and the crippling effects of overly restrictive monetary policy (the infamous ‘Volcker shock’) broke the back or organized labor. As trade union power declined, a crucial mechanism for progressively redistributing income began to fade in significance.

The decline of trade unions did not lead to an economic golden age, as some would have hoped. In the decades after 1980, business investment trended downward, job creation slowed and GDP growth decelerated—a phenomenon often referred to as ‘secular stagnation’. Many economists have wondered why, given business-friendly policies in Washington, investment declined so precipitously after 1980.

My study reveals that America does not suffer from a shortage of investment in the general sense. The American corporate sector has been spending more money than ever, but instead of ploughing resources into job creation and fixed asset investment, historically unprecedented resources are flowing into mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and stock repurchase, the combined effect of which has been slower growth and rising inequality (a finding which also applies to Canada—see here and here).

Unlike investment in fixed assets, which is linked with job creation, M&A merely redistributes corporate ownership claims between proprietors. The motivation for M&A is straightforward: large firms absorb the income stream of the firms they acquire while reducing competitive pressure, which increases their market power.

In the century spanning 1895 through 1990, for every dollar spent on fixed asset investment, American business spent an average of just 18 cents on M&A. In the period since 1990, for every dollar spent on fixed asset investment an average of 68 cents was spent on M&A—a four-fold increase.

The explosion of M&A since 1990 has led to the concentration of corporate assets (power, in other words). In 1990 the 100 largest American firms controlled 9 percent of total corporate assets. Asset concentration more than doubled over the next two decades, peaking at 21 percent. The creation of a concentrated market structure, which has gone largely unnoticed by the economics profession, is one reason inequality has worsened in recent decades.

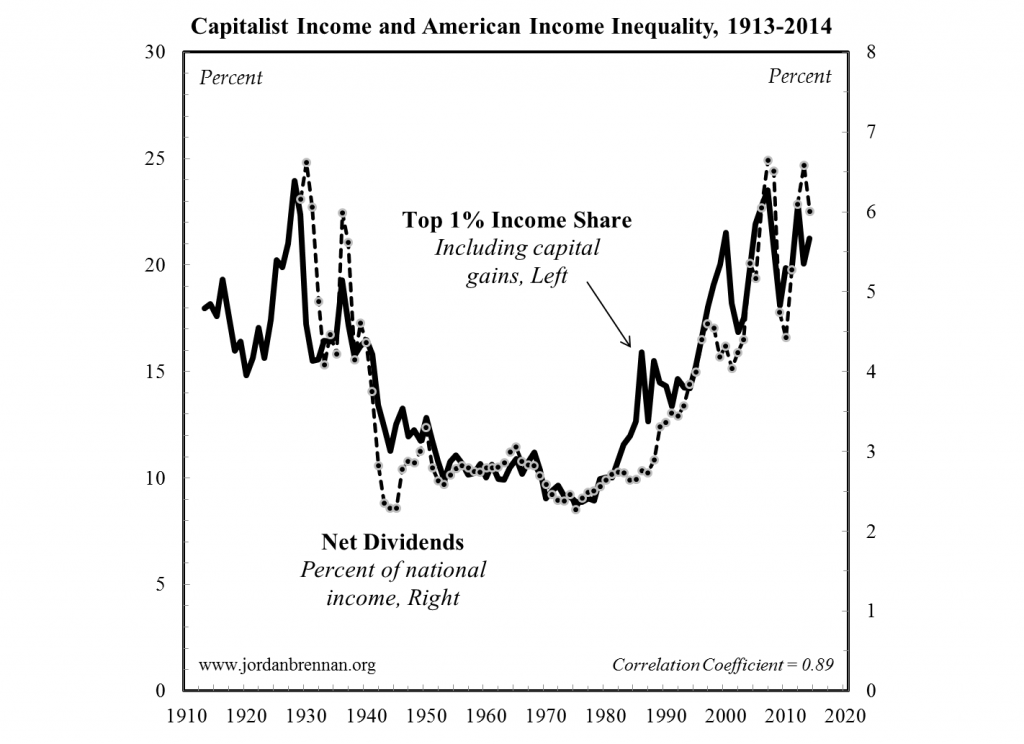

With more market power-generated income at their disposal, large firms have paid comparatively more to shareholders in the form of dividends (the enclosed figure contrasts the income share of the richest 1 percent of Americans with the dividend share of national income).

At the same time, the 100 largest firms have spent more repurchasing their own stock than they have on machinery and equipment. And because many executives have stock options in their contracts, the share price inflation associated with stock repurchase has led to soaring executive compensation.

It is in this manner that increasing corporate concentration has simultaneously slowed growth and exacerbated inequality. None of these developments are inevitable, but if we are to meaningfully confront the dual problem of secular stagnation and soaring inequality we must begin to understand the role that power plays in driving these trends.

The Oligarchy Economy: Concentrated Power, Income Inequality, and Slow Growth

Gary Reber Comments:

Author Jordan Brennan, a labor economist for Canada’s largest private sector labor union, while not clear in his terminology, basically presents the case that the cause of economic inequality is concentrated capital asset ownership (though he tends to represent this as “market power”).

The problem with conventional-thinking economist, Brennan included, is they do not distinguish between the human factor and the non-human factor of production, thus couch income disparities in narrow labor productivity measures. But those measure are wrong if they were to view economic value created through human and non-human contributions. Of course, the non-human contributions have to do with the ownership rights to property.

On the other hand, binary economics recognizes that there are two independent factors of production: humans (labor workers who contribute manual, intellectual, creative and entrepreneurial work) and non-human capital (productive land; structures; infrastructure; tools; machines; robotics; computer processing; certain intangibles that have the characteristics of property, such as patents and trade or firm names; and the like which are owned by people individually or in association with others).

The reason the wealthy are more wealthy than ever is because they have increasingly accumulated more ownership of wealth-creating, income-producing capital assets, whether through direct investment or the acquisition of companies to form a market power (monopoly). Both are the result of using retained earnings and debt financing, neither of which create any new owners, but enrich the same wealthy ownership class.

The role of physical productive capital is to do ever more of the work, which produces wealth and thus income to those who own productive capital assets. Full employment is not an objective of businesses nor is conducting business statically in terms of geographical location. Companies strive to achieve cost efficiencies to maximize profits for the owners, thus keeping labor input and other costs at a minimum.

No where does Brennan, as well as other economists, provide a solution that would ensure that future viable investments in the formation of new capital assets are financed using mechanisms that provide interest-free capital credit to EVERY child, woman, and man for the exclusive purpose of acquiring future capital assets on the basis that the investments will generate their own income stream and pay for themselves and once paid for will go on producing income indefinitely with proper maintenance and with restoration in the technical sense through research and development. Such financial mechanism would use commercial capital credit and reinsurances (ala the Federal Housing Administration concept) as the substitute for the present requirement of “past savings” (accumulated capital wealth) to protect the credit issuers from the risk of failure to return the expected yield from which to repay the loan.

Unfortunately, as a labor economist for a labor union, Brennon appears not to be an advocate for transforming the labor movement to a producers’ ownership union movement and embrace and fight for this workers owning stakes in the corporations that employee them. Instead, he laments the decline of the labor unions, and blames such on rising economic inequality.

Unfortunately, at the present time the movement is built on one-factor economics — the labor worker. The insufficiency of labor worker earnings to purchase increasingly capital-produced products and services gave rise to labor laws and labor unions designed to coerce higher and higher prices for the same or reduced labor input. With government assistance, unions have gradually converted productive enterprises in the private and public sectors into welfare institutions. Binary economist Louis Kelso stated: “The myth of the ‘rising productivity’ of labor is used to conceal the increasing productiveness of capital and the decreasing productiveness of labor, and to disguise income redistribution by making it seem morally acceptable.”

Kelso argued that unions “must adopt a sound strategy that conforms to the economic facts of life. If under free-market conditions, 90 percent of the goods and services are produced by capital input, then 90 percent of the earnings of working people must flow to them as wages of their capital and the remainder as wages of their labor work… If there are in reality two ways for people to participate in production and earn income, then tomorrow’s producers’ union must take cognizance of both… The question is only whether the labor union will help lead this movement or, refusing to learn, to change, and to innovate, become irrelevant.”

The unions should reassess their role of bargaining for more and more income for the same work or less and less work, and embrace a cooperative approach to survival, whereby they redefine “more” income for their workers in terms of the combined wages of labor and capital on the part of the workforce. They should continue to represent the workers as labor workers in all the aspects that are represented today — wages, hours, and working conditions — and, in addition, represent workers as full voting stockowners as capital ownership is built into the workforce. What is needed is leadership to define “more” as two ways to earn income.

If we continue with the past’s unworkable trickle-down economic policies, governments will have to continue to use the coercive power of taxation to redistribute income that is made by people who earn it and give it to those who need it. This results in ever deepening massive debt on local, state, and national government levels, which leads to the citizenry becoming parasites instead of enabling people to become productive in the way that products and services are actually produced.

When labor unions transform to producers’ ownership unions, opportunity will be created for the unions to reach out to all shareholders (stock owners) who are not adequately represented on corporate boards, and eventually all labor workers will want to join an ownership union in order to be effectively represented as an aspiring capital owner. The overall strategy should assure that the labor compensation of the union’s members does not exceed the labor costs of the employer’s competitors, and that capital earnings of its members are built up to a level that optimizes their combined labor-capital worker earnings. A producers’ ownership union would work collaboratively with management to secure financing of advanced technologies and other new capital investments and broaden ownership. This will enable American companies to become more cost-competitive in global markets and to reduce the outsourcing of jobs to workers willing or forced to take lower wages.

Bottom line: we need to focus on CAPITAL OWNERSHIP CREATION as the solution to economic inequality. Every government policy must be structure to optimally promote creating new capital owners simultaneously with the growth of the economy, without resorting to redistribution of wealth and income.

The end result would be that citizens would become empowered as owners to meet their own consumption needs and government would become more dependent on economically independent citizens, thus reversing current global trends where all citizens will eventually become dependent for their economic well-being on the State and whatever elite controls the coercive powers of government.

Support Monetary Justice at http://capitalhomestead.org/page/monetary-justice.

Support the Capital Homestead Act (aka Economic Democracy Act) at http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-a-plan-for-getting-ownership-income-and-power-to-every-citizen/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-summary/ and http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/ch-vehicles/.