On April 8, 2016, Didier Jacobs writes on Economics:

The 62 richest people in the world own as much wealth as half of humanity. Such extreme wealth conjures images of both fat cats and deserving entrepreneurs. So where did so much money come from?

It turns out, three-fourths of extreme wealth in the US falls on the fat cat side.

A key empirical question in the inequality debate is to what extent rich people derive their wealth from “rents”, which is windfall income they did not produce, as opposed to activities creating true economic benefit.

Economists define “rent” as the difference between what people are paid and what they would have to be paid to do the work anyway. The classical example is the farmer who owns particularly fertile land. With the same effort, she can produce more than other farmers working on land of average productivity. The extra income she gets is a rent. Monopolists also get rent by overcharging customers as compared to what they could charge in competitive markets. More generally, economists have identified a series of “market failures”, which are situations where full competition does not prevail and where someone can therefore overcharge – they would be ready to do the work for less, but lack of competition allows them to make a quick extra buck. Government can alleviate market failures through proper economic regulation; or it can make them worse. Political scientists define “rent-seeking” as influencing government to get special privileges, such as subsidies or exclusive production licenses, to capture income and wealth produced by others.

So how much of extreme wealth derives from rents? It’s a pretty divisive debate, but one that can be resolved with data.

On one hand, Lawrence Mishel and Josh Bivens argue that the income of the top one percent richest Americans comes mainly from executive pay and the financial industry, two sources of income notorious for the market failure of imperfect information between buyers and sellers. CEOs have more information about their company than shareholders and portfolio managers than investors, which allows them to dramatically overcharge.

On the other hand, Steven Kaplan and Joshua Rauh claim that the fast growth of income at the top is broad-based and is better explained by rising returns to talent induced by technological progress and globalization.

Both camps use largely the same data to support rather divergent narratives, and in truth extreme inequality is driven by more than one phenomenon.

Data limitations do not allow us to compute rents anywhere close to accurately. But if I had to give a single number to settle the debate, it is this: when it comes to the very richest Americans (Forbes’ billionaires), 74% of their wealth is derived from rents.

I recently explored this issue in my paper Extreme Wealth Is Not Merited, and found that American industries that produce more billionaire wealth than average relative to their size share one of three characteristics:

- They depend heavily on the state whether through government procurement, licenses, or subsidies, and are therefore prone to rent-seeking. This category includes for instance oil, gas and mining, gambling, or forestry.

- They are plagued by market failures such as imperfect information, like finance, or by the combination of intellectual property and so-called “network externalities”, which create monopolies like those that pervade the IT industry and industries prone to fads like fashion and music.

- The billionaire wealth they have generated is largely inherited.

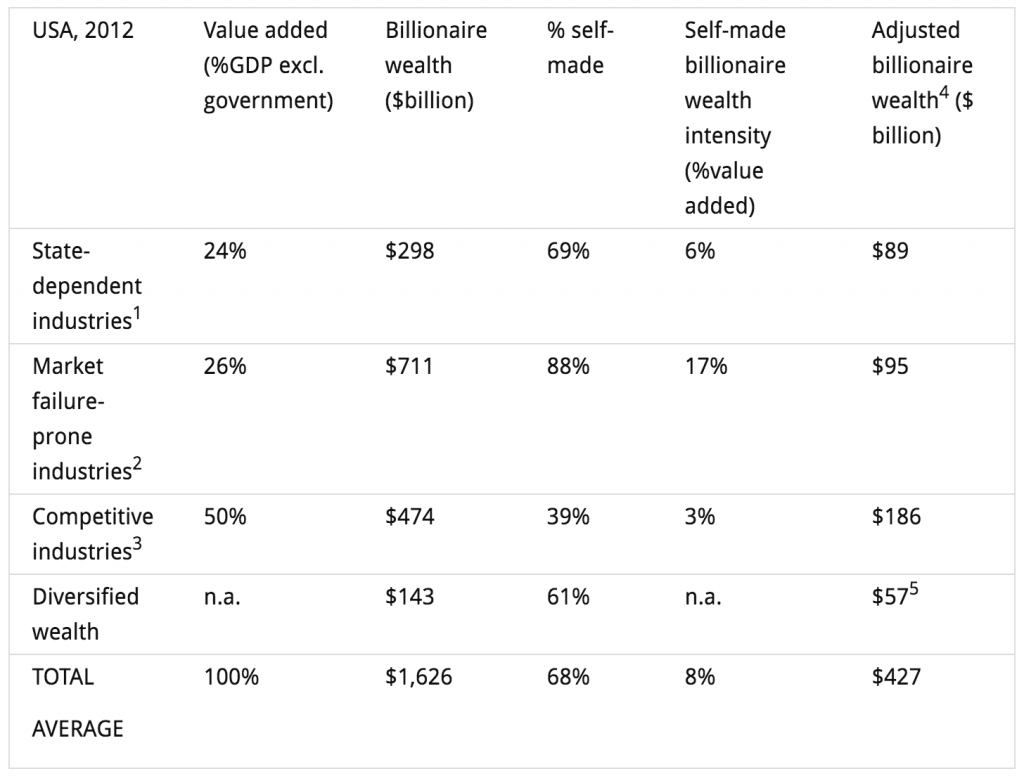

Building on that finding, I calculate that the billionaire wealth generated by these industries in excess of what other industries (considered here as competitive industries) generate represents 74% of America’s billionaire wealth. The table below shows that the industries that are neither dependent on the state nor prone to market failures have a self-made “billionaire wealth intensity” (that is, non-inherited billionaire wealth divided by industry value added – a measure of industry size) of 3%. (So the self-made billionaire wealth we observe in the competitive industries equals 3% of annual production in those industries, or in other words you might say that it has taken 33 years-worth of production to generate today’s billionaire wealth in the competitive industries.) If the whole economy had produced billionaire wealth at that rate, the total American billionaire wealth would have been $427 billion in 2012 instead $1,626 billion, or just 26% as high.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data from Forbes and US Bureau of Economic Analysis. SeeExtreme Wealth Is Not Merited for methodological details and data for each industry.

1 Industries of the cronyism index, namely: casinos; forestry; defense; real estate and construction; ports, airports, infrastructure and pipelines; oil, gas, coal and mining; steel and other metals; utilities and telecoms. Although also in the cronyism index, banking is in the market failure-prone industries.

2 Industries prone to asymmetries of information, namely finance, health care services, and law, and industries prone to network externalities, namely IT, apparel retail, art dealing, broadcasting, motion picture and music, and sports.

3 All other industries.

4 Assuming that all industries had a billionaire wealth intensity equal to the self-made billionaire wealth intensity of competitive industries, namely 3%.

5 Assuming that diversified wealth is invested in each industry according to its weight in GDP.

There are, of course, all sorts of reasons why billionaire wealth intensity varies across industries, not all of which involve rents. However, Joseph Stiglitz counters that the very existence of extreme wealth is an indicator of rents. Competition drives profit down, such that it might be impossible to become extremely rich without market failures. Every good business strategy seeks to exploit one market failure or the other in order to generate excess profit. I discuss in my paper how some of these strategies are more or less harmful than others. While not all the excess billionaire wealth generated by state-dependent or market failure-prone industries may be due to rents, it is also possible that my figure underestimates the proportion of rent in billionaire wealth. After all, the perfect competition of economics textbooks rarely exists in reality and there must be many pockets of rents in what I call the “competitive industries” as well. Given the current state of research in the field, 74% is the best estimate of the proportion of US billionaire wealth derived from rents.

The bottom-line is that extreme wealth is not broad-based: it is disproportionately generated by a small portion of the economy. Economic theory predicts that activities that are prone to rent-seeking or market failures will concentrate wealth, and that is what we observe.

This finding has important moral, economic, and policy implications. To the extent that it is driven by rents as opposed to productive activities, the extreme concentration of wealth we observe is not fair according to a meritocratic conception of social justice. Moreover, because rents do not compensate productive activities, redistributing them through taxes or regulation does not harm the economy, and could even boost economic growth. As wealth inequality has become so extreme, even modest redistribution could have significant positive impact for the poor and the middle class.

They Don’t Just Hide Their Money. Economist Says Most of Billionaire Wealth is Unearned.

Yes, the rich are rich because they own capital assets that produce income. It is a natural right to own and our economy is based on the principle of private property. Somehow this meme implies that owning and deriving income from ownership is unearned. Why because one’s hands or legs are not moving as in contributing their labor? There are thousands of examples of people owning small measures of capital assets that do not require labor. Fundamentally, economic value is created through human and non-human contributions. The problem is that capital asset wealth is concentrated among a tiny wealthy capital ownership class instead of broadly owned. Our economic policy should be to simultaneously create new capital owners with the future growth of the economy and provide equal opportunity for EVERY child, woman, and man to become a capital owner without the requirement of past savings to invest, but through the use of insured, interest-free capital credit, repayable out of the future earnings of the investments––the same means the rich use to continually further concentrate ownership.