On February 12, 2017, Scott Santens writes on Economics:

Almost two centuries ago an idea was born with such explanatory power that it created shock waves across all of human society and whose aftershocks we’re still feeling to this day. It’s so simple and yet so powerful, that after all these years, it remains capable of making people question their very faith.

The idea of which I speak is that through random mutation and natural selection, every living thing around us was created through millions and even billions of years of what is effectively trial and error, not designed by some intelligent creator. It is the process of evolution through natural selection.

It’s almost impossible for many people to accept that everything around us, including our own lives, could ever be the result of trial and error, but that’s what the scientific method has revealed. Mutations happen. Some of them work better than others depending on the environment. A longer beak here and a longer neck there can be the difference between life and death. Successful mutations are passed on. Iterations continue generation after generation. Discovering this process of evolution was one of the great accomplishments of our species. It’s also possibly the most powerful reason to support another world-changing idea — an unconditional basic income.

Let me explain.

Markets as Environments

Our economy is a complex adaptive system. Much like how nature works, markets work. No one central planner is deciding what natural resources to mine, what to make with them, how much to make, where to ship everything to, who to give it to, etc. These decisions are the result of a massively decentralized widely distributed system called “the market,” and it’s all made possible with a tool we call “money” being exchanged between those who want something (demand) and those who provide that something (supply).

Money is more than a decentralized tool of calculation however. It’s also like energy. It powers the entire process like the eating of food powers our own bodies and the sun powers plants. Without food, we starve, and without money, markets starve. A sufficient amount of money for all market participants is absolutely key to the market system for it to work properly.

If you’ve ever played Monopoly this should be apparent. The game would not work if all players started the game with nothing. Some wouldn’t even make it once around the board. Additionally, if no one received $200 for then passing Go, the game would end a lot sooner. Ultimately the game always grinds to a halt once everyone but one person is all out of money, which is inevitable. No money, no purchases, no market, no game. Game over.

Supply and Demand as Trial and Error

With sufficient money however, markets adapt and evolve based on trial and error. Someone thinks of something to create or do. If people like it, it does well. If people don’t like it, it goes away. What does well is modified. If people like the modified version, it does well. If they don’t, it goes away. If they like it enough, the original version goes away. Survival of the fittest we call it. This is the evolution of goods and services, which runs on supply and demand, which both in turn run on money and one other thing — the willingness to take risks.

Risks as Genetic Mutation

Taking risks is equivalent to random genetic mutation in this biological analogy. A new product or service introduced into the market can result in success or failure. The outcome is entirely unknown until it’s tried. What succeeds can make someone rich and what fails can bankrupt someone. That’s a big risk. We traditionally like to think of these risk-takers as a special kind of person, but really they’re mostly just those who are economically secure enough to feel failure isn’t scarier than the potential for success.

As a prime example, Elon Musk is one of today’s most well-known and highly successful risk takers. Back in his college years he challenged himself to live on $1 a day for a month. Why did he do that? He figured that if he could successfully survive with very little money, he could survive any failure. With that knowledge gained, the risk of failure in his mind was reduced enough to not prevent him from risking everything to succeed.

This isn’t just anecdotal evidence either. Studies have shown that the very existence of food stamps — just knowing they are there as an option in case of failure — increases rates of entrepreneurship. A study of a reform to the French unemployment insurance system that allowed workers to remain eligible for benefits if they started a business found that the reform resulted in more entrepreneurs starting their own businesses. In Canada, a reform was made to their maternity leave policy, where new mothers were guaranteed a job after a year of leave. A study of the results of this policy change showed a 35% increase in entrepreneurship due to women basically asking themselves, “What have I got to lose? If I fail, I’m guaranteed my paycheck back anyway.”

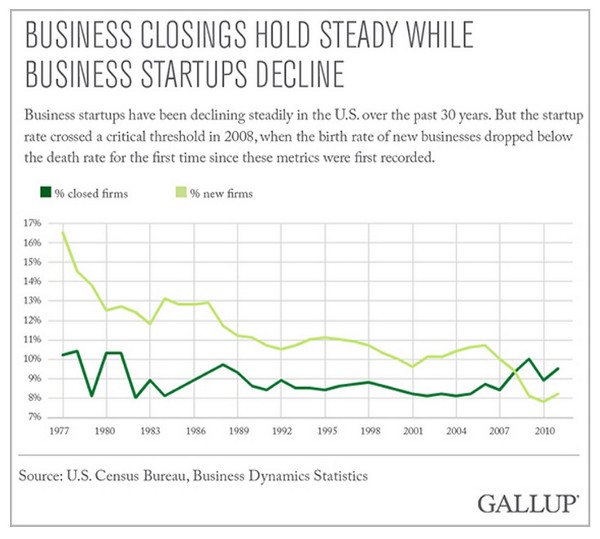

Meanwhile, entrepreneurship is currently on a downward trend. Businesses that were less than five years old used to comprise half of all businesses three decades ago. Now they comprise about one-third. Businesses are also closing their doors faster than new businesses are opening them. Until recently, this had never previously been true here in the US for as long as such data had been recorded. Startup rates are falling. Why? Risk aversion due to rising insecurity.

Growing Insecurity

For decades now our economy has been going through some very significant changes thanks to advancements in technology, and we have simultaneously been actively eroding the institutions that pooled risk like trade unions and our public safety net. Incomes adjusted for inflation have not budged for decades, and the jobs providing those incomes have gone from secure careers to insecure jobs, part-time and contract work, and now recently even gig labor in the sharing economy.

Decreasing economic security means a population decreasingly likely to take risks. Looking at it this way, of course startups have been on the decline. How can you take the leap of faith required for a startup when you’re more and more worried about just being able to pay the rent?

None of this should be surprising. The entire insurance industry exists to reduce risk. When someone is able to insure something, they are more willing to take risks. Would there be as many restaurants if there was no insurance in case of fire? Of course not. The corporation itself exists to reduce personal risk. Entrepreneurship and risk are inextricably linked.Reducing risk aversion is paramount to innovation.

Failure as Evolution

So the question becomes, how do we reduce the risks of failure so that more people take more risks? Better yet, how do we increase the rate of failure? It may sound counter-intuitive, but failure is not something to avoid. It’s only through failure that we learn what doesn’t work and what might work instead. This is basically the scientific method in a nutshell. It’s designed to rule out what isn’t true, not to determine what is true. There is a very important difference between the two.

This is also how evolution works, through failure after failure. Nature isn’t determining the winner. Nature is simply determining all the losers, and those who don’t lose, win the game of evolution by default. So, the higher the rate of mutation, the more mutations can fail or not fail, and therefore the quicker an organism can adapt to a changing environment. In the same way, the higher the rate of failure in a market economy, the quicker the economy can evolve.

There’s also something else very important to understand about failure and success. One success can outweigh 100,000 failures. Venture capitalist Paul Graham of Y Combinator has described this as Black Swan Farming. When it comes to truly transformative ideas, they aren’t obviously great ideas, or else they’d already be more than just an idea, and when it comes to taking a risk on investing in a startup, the question is not so much if it will succeed, but if it will succeed BIG. What’s so interesting is that the biggest ideas tend to be seen as the least likely to succeed.

Now translate that to people themselves. What if the people most likely to massively change the world for the better, the Einsteins so to speak — the Black Swans, are oftentimes those least likely to be seen as deserving social investment? In that case, the smart approach would be to cast an extremely large net of social investment, in full recognition that even at such great cost, the ROI from the innovation of the Black Swans would far surpass the cost.

This happens to be exactly what Buckminster Fuller was thinking when he said, “We must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest.” That is a fact, and it then begs the question, “How do we make sure we invest in every single one of those people such that all of society maximizes its collective ROI?”

What if our insistence on making people earn their living is preventing those one in ten thousand from making incredible achievements that would benefit all the rest of us in ways we can’t even imagine? What if our fears of each other being fully free to pursue whatever most interests us, including nothing, is an obstacle to an explosion of entrepreneurship and truly huge innovations the likes of which have never been seen?

Fear as Death

What it all comes down to is fear. FDR was absolutely right when he said the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Fear prevents risk-taking, which prevents failure, which prevents innovation. If the great fears are of hunger and homelessness, and they prevent many people from taking risks who would otherwise take risks, then the answer is to simply take hunger and homelessness off the table. Don’t just hope some people are unafraid enough. Eliminate what people fear so they are no longer afraid.

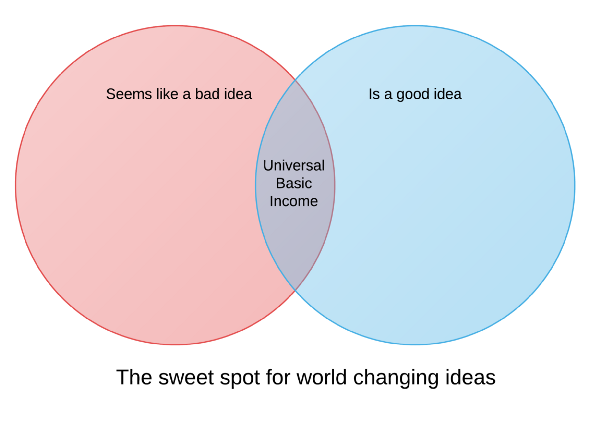

If everyone received as an absolute minimum, a sufficient amount of money each month to cover their basic needs for that month no matter what — an unconditional basic income — then the fear of hunger and homelessness is eliminated. It’s gone. And with it, the risks of failure considered too steep to take a chance on something.

But the effects of basic income don’t stop with a reduction of risk. Basic income is also basic capital. It enables more people to actually afford to create a new product or service instead of just think about it, and even better, it enables people to be the consumers who purchase those new products and services, and in so doing decide what succeeds and what fails through an even more widely distributed and further decentralized free market system.

Such market effects have even been observed in universal basic income experiments in Namibia and India where local markets flourished thanks to a tripling of entrepreneurs and the enabling of everyone to be a consumer with a minimum amount of buying power.

Basic income would even help power the sharing economy. For example, imagine how much an unconditional monthly income would enable people within the Open Source Software (OSS) and free software movements (FSM) to do the unpaid work that is essentially the foundation of the internet itself.

Markets as Democracies

Markets work best when everyone can vote with their dollars, and have enough dollars to vote for products and services. The iPhone exists today not simply because Steve Jobs had the resources to make it into reality. The iPhone exists to this day because millions of people have voted on it with their dollars. Had they not had those dollars, we would not have the iPhone, or really anything else for that matter. Voting matters. Dollars matter.

Evolution teaches us that failure is important in order to reveal what doesn’t fail through the unfathomably powerful process of trial and error. We should apply this to the way we self-organize our societies and leverage the potential for universal basic income to dramatically reduce the fear of failure, and in so doing, increase the amount of risks taken to accelerate innovation to new heights.

Failure is not an option. Failure is the goal. And fear of failure is the enemy.

It’s time we evolve.

Universal Basic Income Accelerates Innovation by Reducing Our Fear of Failure

Gary Reber Comments:

Basically, the author of this article, Scott Santens, is arguing for EVERY person to receive an unconditional basic income, which would serve as a foundation to take risks to be entrepernaural and start businesses. Santens does not define person; does that included every child or are their age restrictions? Nor does he define the basic amount of money that EVERY person would receive monthly, unconditionally. These are important parameters to define as there is a cost to this proposal because it would be funded by redistribution of wealth or by incurring more non-asset government debt.

Santens does not appear to understand the players in an economy. There are two independent factors of production: humans (labor workers who contribute manual, intellectual, creative and entrepreneurial work) and non-human capital (land; structures; infrastructure; tools; machines; robotics; computer processing; certain intangibles that have the characteristics of property, such as patents and trade or firm names; and the like which are owned by people individually or in association with others). Fundamentally, economic value is created through human and non-human contributions.

Santens also does not appear to understand money and its role in an economy. Real physical productive capital isn’t money; it is measured in money (financial capital), but it is really producing power and earning power through ownership of the non-human factor of production. Financial capital, such as stocks and bonds, is just an ownership claim on the productive power of real capital. In the law, property is the bundle of rights that determines one’s relationship to things. As binary economists Louis Kelso and Patricia Hetter put it, “Money is not a part of the visible sector of the economy; people do not consume money. Money is not a physical factor of production, but rather a yardstick for measuring economic input, economic outtake and the relative values of the real goods and services of the economic world. Money provides a method of measuring obligations, rights, powers and privileges. It provides a means whereby certain individuals can accumulate claims against others, or against the economy as a whole, or against many economies. It is a system of symbols that many economists substitute for the visible sector and its productive enterprises, goods and services, thereby losing sight of the fact that a monetary system is a part only of the invisible sector of the economy, and that its adequacy can only be measured by its effect upon the visible sector.”

The role of physical productive capital is to do ever more of the work, which produces wealth and thus income to those who own productive capital assets. Over the past century there has been an ever-accelerating shift to productive capital — which reflects tectonic shifts in the technologies of production. People invented “tools” to reduce toil, enable otherwise impossible production, create new highly automated industries, and significantly change the way in which products and services are produced from labor intensive to capital intensive — the core function of technological invention and innovation. Kelso attributed most changes in the productive capacity of the world since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution to technological improvements in our capital assets, and a relatively diminishing proportion to human labor. Capital, in Kelso’s terms, does not “enhance” labor productivity (labor’s ability to produce economic goods). In fact, the opposite is true. It makes many forms of labor unnecessary. Because of this undeniable fact, Kelso asserted that, “free-market forces no longer establish the ‘value’ of labor. Instead, the price of labor is artificially elevated by government through minimum wage legislation, overtime laws, and collective bargaining legislation or by government employment and government subsidization of private employment solely to increase consumer income.” An unconditional basic income is yet another form of government subsidization and leaves the ownership of productive capital assets concentrated among a wealthy capital ownership class (the 1 percent).

Furthermore, according to Kelso, productive capital is increasingly the source of the world’s economic growth and, therefore, should become the source of added property ownership incomes for all. Kelso postulated that if both labor and capital are independent factors of production, and if capital’s proportionate contributions are increasing relative to that of labor, then equality of opportunity and economic justice demands that the right to property (and access to the means of acquiring and possessing property) must in justice be extended to all.

The reason that people are in poverty or earn insufficient income to support their lives is because production does not equate to consumption. After all, the purpose of production is consumption. It is the exponential disassociation of production and consumption that is the problem in the United States economy, and the reason that ordinary citizens must gain access to productive capital ownership to improve their economic well-being.

In today’s economy, the capitalism practiced is institutionalizes greed (creating concentrated capital ownership, monopolies, and special privileges). It is about the ability of greedy rich people to manipulate the lives of people who struggle with declining labor worker earnings and job opportunities, and then accumulate the bulk of the money through monopolized productive capital ownership. Our scientists, engineers, and executive managers who are not owners themselves, except for those in the highest employed positions, are encouraged to work to destroy employment by making the capital “worker” owner more productive. How much employment can be destroyed by substituting machines for people is a measure of their success – always focused on producing at the lowest cost. Only the people who already own productive capital are the beneficiaries of their work, as they systematically concentrate more and more capital ownership in their stationary 1 percent ranks. Yet the 1 percent are not the people who do the overwhelming consuming. The result is the consumer populous is not able to get the money to buy the products and services produced as a result of substituting machines for people. And yet you can’t have mass production without mass human consumption made possible by “customers with money.”

Kelso postulated: “When consumer earning power is systematically acquired in the course of the normal operations of the economy by people who need and want more consumer goods and services, the production of goods and services should rise to unprecedented levels; the quality and craftsmanship of goods and services, freed of the corner-cutting imposed by the chronic shortage of consumer purchasing power, should return to their former high levels; competition should be brisk; and the purchasing power of money should remain stable year after year.”

Without this necessary balance hopeless poverty, social alienation, and economic breakdown will persist, even though the American economy is ripe with the physical, technical, managerial, and engineering prerequisites for improving the lives of the 99 percent majority. Why? Because there is a crippling organizational malfunction that prevents making full use of the technological prowess that we have developed. The system does not fully facilitate connecting the majority of citizens, who have unsatisfied needs and wants, to the productive capital assets enabling productive efficiency and economic growth.

I agree with Santens that the vast majority of American need to earn more income. I believe we can facilitate that need and create an economy that can support general affluence for EVERY citizen. To do so will require instituting capital credit mechanisms that will implement the goal of broadening productive capital ownership in ways wholly compatible with the U.S. Constitution and the protection of private property, simultaneously with the growth of the economy, without the requirement of “past savings” (what only the wealthy have) or redistribution from the wealthy to the non-wealthy or subsidization by government.

Without a policy shift to broaden productive capital ownership simultaneously with economic growth, further development of technology and globalization will undermine the American middle class and make it impossible for more than a minority of citizens to achieve middle-class status.

We need to create economic democracy. The way to do this is to allocate an annual amount of new asset-backed money (facilitated by the Federal Reserve through its discount window authorized under Section 13(2) of the Federal Reserve Act), based on the projection of GDP growth in any given year, to EVERY child, woman and man for the exclusive use to acquire ownership in viable new productive capital formation by the corporations growing the economy. These new assets are expected to earn a continuing flow of profit for whoever owns the assets. The financial mechanisms needed to implement such broadening of capital ownership simultaneously with the growth of the economy are interest-free capital credit, repayable solely out of the future earnings of the investments. In addition to determining that the investments are viable and that the business corporations are credit worthy and reliably expected to generate earnings sufficient to make loan repayments, there needs to be security against loan default. Thus, for the lender (a local bank) to make the loan, security must be provided.

Instead of the current requirement of “past savings” (assets pledged as security), to solve the security issue, the risk can be absorbed by capital credit insurance or commercial risk insurance. and reinsurance (ala the Federal Housing Administration concept). Thus, in order to achieve national economic democracy, we need a way to handle risk management in finance by broadly insuring the risks. Such capital credit insurance would substitute for the security demanded by lenders to cover the risk of non-payment, thus enabling the poor and others with no or few assets (the 99 percenters) to overcome the collateralization barrier that excludes the non-halves from access to wealth-creating, income-generating productive capital.

We will need to lift ownership-concentrating Federal Reserve System credit barriers and other institutional barriers that have historically separated owners from non-owners and link tax and monetary reforms to the goal of expanded capital ownership. Removing barriers that inhibit or prevent ordinary people from purchasing capital that pays for itself out of its own future earnings is paramount as an actionable policy. This can be done under the existing legal powers of each of the 12 Federal Reserve regional banks, and will not add to the already unsustainable debt of the Federal Government or raise taxes on ordinary taxpayers. We need to free the system of dependency on Wall Street and the accumulated savings and money power of the rich and super-rich who control Wall Street. The Federal Reserve System has stifled the growth of America’s productive capacity through its monetary policy by monetizing public-sector growth and mounting federal deficits and “Wall Street” bailouts; by favoring speculation over investment; by shortchanging the capital credit needs of entrepreneurs, inventors, farmers, and workers; by increasing the dependency with usurious consumer credit; and by perpetuating unjust capital credit and ownership barriers between rich Americans and those without savings.

The Federal Reserve Bank should be used to provide interest-free capital credit (including only transaction and risk premiums) and monetize each capital formation transaction, determined by the same expertise that determines it today — management and banks — that each transaction is viably feasible so that there is virtually no risk in the Federal Reserve. The first layer of risk would be taken by the commercial credit insurers, backed by a new government corporation, the Capital Diffusion Reinsurance Corporation, through which the loans could be guaranteed. This entity would fulfill the government’s responsibility for the health and prosperity of the American economy.

The Federal Reserve Board is already empowered under Section 13(2) of the Federal Reserve Act to reform monetary policy to discourage non-productive uses of credit, to encourage accelerated rates of private sector growth, and to promote widespread individual access to productive credit as a fundamental right of citizenship. The Federal Reserve Board needs to re-activate its discount mechanism to encourage private sector growth linked to expanded capital ownership opportunities for all Americans.

Over time, EVERY child, woman and man would accumulate a significant, full-voting, full-dividend earnings payout of stocks, which after loan payback, would go on producing income indefinitely with proper maintenance and with restoration in the technical sense through research and development.

The end result would be that citizens would become empowered as owners to meet their own consumption needs and government would become more dependent on economically independent citizens, thus reversing current global trends where all citizens will eventually become dependent for their economic well-being on the State and whatever elite controls the coercive powers of government.

Support Monetary Justice at http://capitalhomestead.org/page/monetary-justice.

Support the Capital Homestead Act (aka Economic Democracy Act) at http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-a-plan-for-getting-ownership-income-and-power-to-every-citizen/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-summary/ and http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/ch-vehicles/.