Maybe he had a point. Photographer: Uwe Meinhold/AFP/Getty Images

Automation and offshoring may be conspiring to reduce labor’s share of income.

On September 25, Noah Smith writes on Bloomberg:

Back in April, I wrote about one of the most troubling mysteries in economics, the falling labor share. Less of the income the economy produces is going to people who work, and more is going to people who own things.

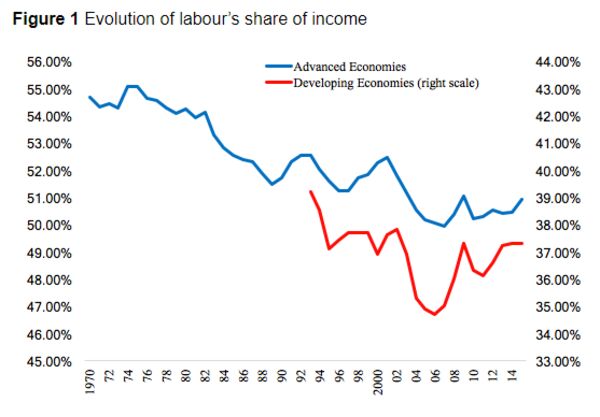

Less of the Pie for Labor

Share of GDP received by workers.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

This trend is worrying because it contributes to increased inequality — poor people own much less of the land and capital in the economy than rich people do. The devaluation of workers could also increase unemployment, social unrest and general malaise. No one would like to see capitalism transform into the kind of dystopia envisioned by Karl Marx. That’s why even though the decline in labor’s share has so far been relatively modest, economists are racing to diagnose the cause before the problem gets any worse.

Recently, a lot of attention has focused on the idea that monopoly power might be causing the shift. But the famous paper that draws this connection — by David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence Katz, Christina Patterson and John Van Reenen — also shows that it can account for perhaps only 20 percent of the change. This means other possible explanations for labor’s decline, like increasing automation or globalization, need to be re-examined.

Economists Mai Dao, Mitali Das, Zsoka Koczan and Weicheng Lian of the International Monetary Fund argue that the culprit is not automation or offshoring alone, but the interaction between the two. As evidence, they note that the labor share has been falling not just in rich nations, but in developing countries as well. Here is a figure from their paper:

If globalization were purely to blame, this wouldn’t be happening. Standard trade theories imply that because rich countries have a lot of capital and poor countries have a lot of labor, when these countries start to trade, labor’s share of income should go down in the countries where it used to be scarce — i.e., the rich world — but should rise in the poor countries where it was previously abundant. That’s not what’s happening.

Meanwhile, if automation is just now starting to make workers obsolete, developing countries shouldn’t be experiencing the fall in labor share at the same time, because in technological terms they’re decades behind the rich countries. The authors confirm that investment goods — machines, vehicles, computers, etc. — haven’t really gotten much cheaper in poor countries, as they have in rich ones. So the puzzle really boils down to this: Why is the labor share falling in the developing world?

Dao and her co-authors offer a hypothesis. It has to do with the types of industries that exist in poor countries before and after trade gets opened up. When poor countries are isolated from the global economy, they tend to specialize in things that rely on a lot of cheap labor — farming, low-end services and simple labor-intensive manufacturing. Local landlords and other capital owners do well, but don’t have a chance to get truly rich, because any investment in machinery or technology can be undercut by a flood of low-wage workers. So they don’t bother making the investments in the first place. This dearth of capital spending is exacerbated by rudimentary or dysfunctional financial systems.

But when trade opens up, the rich countries start offshoring manufacturing jobs to the poor countries. These jobs offer better opportunities for workers, but much better opportunities for capitalists. Even as capitalists in the U.S. or Japan or France get rich cutting labor costs by shipping jobs to China, Chinese capitalists get rich because they’re finally able to amass huge business empires.

The IMF economists also predict that global financial integration should help alleviate the pressure on labor in poor countries. If American, European, Japanese and Taiwanese companies are able to invest in a developing country like China, the inflow of foreign money will boost incomes for local workers and compete down the profits of local capital owners.

So what about rich countries? Here, the argument is that automation and globalization are working together — companies in rich countries can ship labor-intensive manufacturing jobs in electronics assembly, toys and clothing to China and Bangladesh, while buying advanced machine tools and robots to do more high-end manufacturing of things like microprocessors and airplanes. As a result, workers in rich countries where routine jobs were more common were hit harder by both free trade and the advent of cheap automation.

In other words, the two most conventional explanations for rising inequality and falling wages might both be correct. A perfect storm of robots and free trade — and some monopoly power to boot — could be shifting power from the proletariat to the capitalists. With all these factors at work, maybe the real puzzle is why workers aren’t doing even worse than they are.

https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-09-20/why-workers-are-losing-to-capitalists

Gary Reber Comments:

What we are experiencing is the ever-greater substitution of machines for human labor and at the same time greater world-wide competition to produce goods, products and services at the lowest cost. This makes for a poor position for those (the vast majority) who can only depend on their labor to earn income. That being the reality, what really makes wage slaves is being without capital ownership in any significant degree. Capital is the non-human factor of production. Fundamentally, economic value is created through human and non-human contributions. In simple terms, there are two independent factors of production: humans (labor workers who contribute manual, intellectual, creative and entrepreneurial work) and non-human capital (land; structures; infrastructure; tools; machines; robotics; computer processing; certain intangibles that have the characteristics of property, such as patents and trade or firm names; and the like which are owned by people individually or in association with others). With capital carrying out most production these days, and the market rate of wages declining in value relative to the cost of capital, what locks people into the wage system in which most people get the bulk of their income from wages is lack of access to capital credit, not the wages, per se.

Yet a just wage is mandatory in any system. Non-owning labor must be compensated fairly, but it is time for the abolition of the wage system, not the abolition of wages. And while ideally a just wage should be defined as the rate determined by the free market, this can only be achieved with equality of bargaining position, with the employer (owner) and the employee entering into free agreements.

What about the exceptions, however? What happens when the free market rate is insufficient for the worker to meet ordinary expenses, or something interferes with the free market in labor, e.g., when the propertyless laborer is forced to take less than justice demands simply because he is in a bad bargaining position?

The difference must be made up of employer charity to ensure that the worker is able to meet ordinary expenses adequately, so that justice is completed and fulfilled by charity.

But, of course, this is not reality. Employers are always seeking to produce at the lowest possible cost, while maintaining the level of quality demanded by the market. From the employer-owner’s perspective, the problem with paying workers more than the free market rate of wages is it increases costs to the consumer (who is usually the worker under another hat). After all, full employment or paying wages higher than the market rate are not objectives of businesses nor is conducting business statically in terms of geographical location (outsourcing). Companies strive to achieve cost efficiencies to maximize profits for the owners (the reason the owners are in business), thus keeping labor input and other costs at a minimum. They strive to minimize marginal costs, the cost of producing an additional unit of a good, product or service once a business has its fixed costs in place, in order to stay competitive with other companies racing to stay competitive through technological innovation. Reducing marginal costs enables businesses to increase profits, offer goods, products and services at a lower price (which people as consumers seek), or both. Increasingly, new technologies are enabling companies to achieve near-zero cost growth without having to hire people. Thus, private sector job creation in numbers that match the pool of people willing and able to work is constantly being eroded by physical productive capital’s ever increasing role.

The result is that the price of products and services are extremely competitive as consumers will always seek the lowest cost/quality/performance alternative, and thus for-profit companies are constantly competing with each other (on a local, national and global scale) for attracting “customers with money” to purchase their products or services in order to generate profits and thus return on investment (ROI).

Over the past century there has been an ever-accelerating shift to productive capital — which reflects tectonic shifts in the technologies of production. The mixture of labor worker input and capital worker input has been rapidly changing at an exponential rate of increase for over 239 years in step with the Industrial Revolution (starting in 1776) and had even been changing long before that with man’s discovery of the first tools, but at a much slower rate. Up until the close of the nineteenth century, the United States remained a working democracy, with the production of products and services dependent on labor worker input. When the American Industrial Revolution began and subsequent technological advances amplified the productive power of non-human capital, plutocratic finance channeled its ownership into fewer and fewer hands, as we continue to witness today with government by the wealthy evidenced at all levels.

People invented “tools” to reduce toil, enable otherwise impossible production, create new highly automated industries, and significantly change the way in which products and services are produced from labor intensive to capital intensive — the core function of technological invention and innovation. Kelso attributed most changes in the productive capacity of the world since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution to technological improvements in our capital assets, and a relatively diminishing proportion to human labor. Capital does not “enhance” labor productivity (labor’s ability to produce economic goods). In fact, the opposite is true. It makes many forms of labor unnecessary. Because of this undeniable fact, according to binary economist Louis Kelso, “free-market forces no longer establish the ‘value’ of labor. Instead, the price of labor is artificially elevated by government through minimum wage legislation, overtime laws, and collective bargaining legislation or by government employment and government subsidization of private employment solely to increase consumer income.”

Furthermore, according to Kelso, productive capital is increasingly the source of the world’s economic growth and, therefore, should become the source of added property ownership incomes for all. Kelso postulated that if both labor and capital are independent factors of production, and if capital’s proportionate contributions are increasing relative to that of labor, then equality of opportunity and economic justice demands that the right to property (and access to the means of acquiring and possessing property) must in justice be extended to all. Yet, sadly, the American people and its leaders still pretend to believe that labor is becoming more productive, and ignore the necessity to broaden personal ownership of wealth-creating, income-producing capital assets simultaneously with the growth of the economy.

We need to shift to a democratic growth economy. Such a future economy, based on Kelso’s binary economics (human and non-human productive inputs), the ownership of productive capital assets would be spread more broadly as the economy grows, without taking anything away from the 1 to 10 percent who now own 50 to 90 percent of the corporate capital asset wealth. Instead, the ownership pie would desirably get much bigger and their percentage of the total ownership would decrease, as ownership gets broader and broader, benefiting EVERY citizen (children, women and men), including the traditionally disenfranchised poor and working and middle class. Thus, productive capital income, from full earnings dividend payouts, would be distributed more broadly and the demand for goods, products and services would be distributed more broadly from the earnings of capital and result in the sustentation of consumer demand, which will promote economic growth and more profitable enterprise. That also means that society can profitably employ unused productive capacity and invest in more productive capacity to service the demands of an environmentally responsible growth economy. As a result, our business corporations would be enabled to operate more efficiency and competitively, while broadening wealth-creating, income-producing ownership participation, creating new capitalists and jobs and “customers with money” to support the goods, products and services being produced.

And how to bring about this state of affairs? Capital Homesteading suggests one way.

Support the Capital Homestead Act (aka Economic Democracy Act and Economic Empowerment Act) at http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-a-plan-for-getting-ownership-income-and-power-to-every-citizen/, http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/capital-homestead-act-summary/ and http://www.cesj.org/learn/capital-homesteading/ch-vehicles/.